BAHIA!!!

Brazil's "Most African State" has shaped celebrations all over the country - and the world

In the spring of 2013, members of the Pakistani Taliban began a series of lethal attacks on doctors attempting to immunize children against polio; the jihadists believed the vaccine was a western subterfuge designed to sterilize Muslims. Within a decade, extremists of a more occidental bent stoked a similar paranoia about Covid vaccines. It should come as little surprise that many of these same individuals rail against the notion of man-made climate change, a mountain of evidence notwithstanding. Meanwhile, there remain those who reject the geological theory of continental drift.

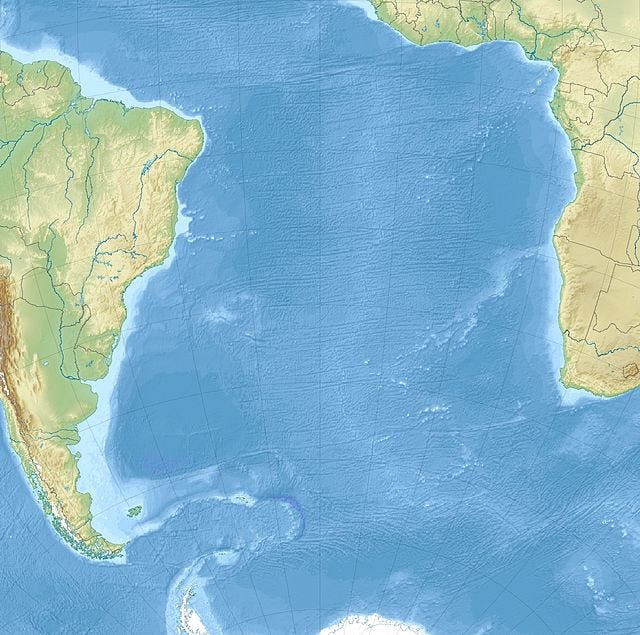

Of all these strains of crackpot contrarianism, the last is perhaps the least explicable. To grasp the dynamics of global warming or disease transmission requires a modicum of abstract thinking. The evidence for geological change, on the other hand should be apparent to anyone who has glanced at a map of the world. Most models suggest that the coast of Bahia, in northeast Brazil, was once adjacent to Gabon in West Africa, separating some 130 million years ago years ago, and arriving at its current position around 20 million years ago. Salvador, the capital of Bahia, is about 5100 kilometers by air from Lagos. In other words, it is much closer Nigeria’s largest city than it is to Lisbon, New York or Mexico City.

Setting aside the realm of tectonic fact, Bahia remains the most African of Brazil’s states in terms of culture and demography. In the 2006 national census, roughly 48% of Brazilians claimed some African ancestry. In Salvador, that figure rises to 85%. One sees this influence in handicrafts sold in the city markets, and in kitchens. Bahian cuisine makes liberal use of ingredients like dried shrimp, coconut, and dende, a fragrant palm oil. Acarajes, a type of bean fritter fried in dende, are a popular street food, and are also consumed as part of Candomble, an Afro-Brazilian faith particularly strong in Salvador.

In the United States, the history of popular music is largely the story of Black migration from the rural South, especially the Mississippi delta. After the Civil War, former slaves and their descendants moved north and west. Carrying instruments and traditions, adapting to new circumstances, they shaped jazz and the blues, rock ‘n’ roll and funk, disco and rap. Brazil saw a similar exodus in the opposite direction.

Slavery in Brazil began earlier than in the USA, and persisted for a generation longer. Abolition was not completed until 1888, and this hastened the demise of the sugar economy in the northeastern states. Bahia’s cane plantations had long been under pressure from foreign competition and domestic policies favoring other cash crops. Granted their freedom but lacking education, some Afro-Brazilians were forced to accept slave-like conditions on coffee plantations to the south. Other flocked to Sao Paulo, Rio de Janeiro, and other growing cities.

Samba first emerged in Rio during the early 20th centuries. Record companies and radio stations broadcasting from the city helped make it into the quintessential sound of the Federative Republic. Most agree that that the style began in Praca Once and other neighborhoods populated by migrants from Bahia. Blending Samba rhythms with American jazz, Bossa Nova embodied Carioca cool. The “new flair” was largely the product of affluent districts around the posh beaches of Ipanema and Copacabana. Undeniably, it would not have evolved in the same way without the influence of Joao Gilberto, a white Bahian who first came to Rio in 1950.

Of course, African Americans did not forsake the South entirely, and the collapse of northeastern sugar did not leave Bahia vacant. The state continued to be a hotspot for musical innovation, including the catch-all category of Musica Popular Brasilieira, or MPB. In the late 1960s and 70’s, the Tropicalia movement fused folk elements with global psychedelia. Tropicalia was embraced nationally by young people who bristled beneath the military dictatorship of the times, but artists from the northeast were among its leading lights, including Gilberto Gil and Caetano Veloso. The pop surrealism that characterized many of the lyrics provided an outlet when more direct forms of protest were met with brutal repression.

Abstraction has its limits, however, and Gil and Veloso were both forced into exile for many years. It is an indicator of democratization that, between 2002 and 2006 Gil joined the government as Minister of Culture, helping to officially designate samba as a “National Artistic Patrimony”.

Musical heritage was celebrated in 2013, when the guitarra baiana, or Bahian guitar, served as the theme for Salvador’s Carnival season. Having only five strings and a shortened fretboard, the instrument may at first seem to resemble a toy. Yet in the hands of skilled player, it unleashes a wail worthy of Jimi Hendrix at his pyrotechnic best. The present form was produced by Armendinho Macedo in the 1970s, but its roots are much older.

The Bahian Guitar is descended from the pau eletrico, or “electric log” which was created in the early 40s by Macedo’s father Osmar and Adolfo “Dodo” Nascimento. While amplified guitars had been used by jazz bands for some time, the pau – which was tuned like a mandolin – was completely solid-bodied, and a true Bahian original. Although a patent was never filed, most musicologists agree that it was developed independently of the instruments created around the same time by Les Paul and Leo Fender in the USA.

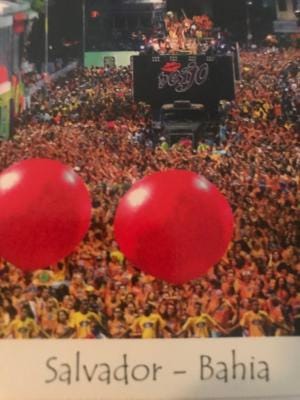

The electric log and its inventors have been immortalized in Salvador’s Carnaval, which revolves around three main circuitos or routes. The Dodo Circuit unfolds by the beaches of Barra and Ondina, while the Circuit of Osmar rolls through the downtown business district to the lush urban park known as Campo Grande. A third circuit runs close to the city’s historic center. Narrow colonial streets mean the scale is reduced, and the relative intimacy of the Batatinha circuit makes it popular with adults of a certain age, as well as families with small children. This reputation, of course, makes it anathema for the young and pretty people shaking it around Osmar and Dodo. However, In the final analysis, this is the very meaning of culture, and of Carnival – the transmission of aesthetic values from one generation to the next.

Batatinha can be translated as “small potatoes”, but the level of joy is massive all over Salvador during the six days when Carnaval is formally celebrated. Stages are set up around the city, where revelers can take in ensembles of traditional and pop music, dance troupes, and exhibitions of capoeira, the graceful form of martial arts originated by enslaved Africans in Brazil’s northeast. One encounters impromptu processions dancing, drumming and careening at any hour of the day or night.

Bahia’s Carnaval offers enjoyments for all tastes and inclinations, but there is no denying that for sheer spectacle, nothing surpasses the Trio Eletrico. In current usage, the term refers, not to a particular configuration, but to the motorized vehicles used to transport musicians as they perform. In the earliest years, this may have included guitar backed up by a rhythm section, with or without vocals. Over the decades, trios grew in both size and sophistication. Today, they are massive stages on wheels, tricked out with lights and sound systems that match anything seen in an arena or theatre. Tractor cabs, which elsewhere might haul transcontinental cargo, ferry the biggest Brazilian and international stars, to the gyrating delight of the masses.

During Carnaval businesses along the parade route typically board up their windows, effectively making entire blocks into resonating chambers. To rest against the plywood as a trio passes, bass thumping at 100 decibels or more, is to truly understand the notion of feeling the beat.

In truth, “parade route” hardly conveys the spirit of Salvador’s circuitos. While the Portuguese percurso do desfile is a literal translation of the English idiom, the connotations are completely different. In more northerly latitudes, the word parade suggests a more-or-less continuous amalgam of high-school bands, floats, and local politicians waving from convertible limousines. The general public is invited to look on from behind barricades. In Bahia, the situation is far more fluid. During the inevitable delays between attractions, spectators freely cross the road to purchase refreshments, visit friends or sanitary facilities, or simply view things from another angle. There may be a break in the music, but there’s no break in the exuberance. In many ways, being at the parade is more important that watching it.

That doesn’t mean that chaos reigns. There is a fairly heavy police presence. Brazilian police have a not entirely unfounded reputation for corruption and brutality. In Bahia, at least, they do a decent job of keeping the peace. During Carnaval, however, their role tends to be reactive rather than restrictive. Order, such as it is, is maintained by the paraders themselves.

In Salvador, as in many parts of the country, the essential carnival grouping is not the samba school, but the bloco. While many have roots in particular neighborhoods or civic associations, most blocos welcome the public. For widely variable fees, revelers can purchase an abada – a t-shirt or similar vestment – allowing them to dance alongside, or upon, a trio electrico. Members of the bloco are separated by the wider masses by means of the corda, a long rope carried to mark the perimeter of the procession. In addition to this “protection” the abada entitles its wearer to beverages, snacks, and other amenities; some trios even have air-conditioned sections for when the heat of dancing in the street becomes too much.

For those with the cash, but not necessarily the energy, to join a bloco, there is the option to visit a camarote. The term is sometimes translated as “cabin”, but that doesn’t do justice to these seasonal pleasure domes, located at key viewing points. Some are private apartments customized for the enjoyment of paying guests. There are also purpose-built structures appointed with any number of luxuries, including food stalls and fine dining options, even spas and beauty salons.

Joining a bloco or visiting a camarote each have their charms, but it is possible to enjoy Salvador’s Carnaval without spending a single centavo – but with beer cheaper than water, few exercise such thrift. The multitudes who party without benefit of abada are referred to as pipoca, or “popcorn”. While the phrase may seem vaguely classist, Salvador’s Carnaval remains eminently democratic. Many blocos, such as Eva or Chiclete com Banana, may designate a day when they roll without cordas, and anybody can come along. Even those who could afford to do so seldom spend all six days behind the ropes or in a viewing stand. Not being bound to a particular locale or route means being free to ramble through the jubilation in all its diversity.

Some blocos are more commercially oriented that others, and naturally those that charge the highest fees are the ones that tend to attract the most popular entertainers. Others, however, are more focused on particular social or cultural aims. Of the latter, few are more cherished than Olodum.

Rolling through the streets at Carnaval, Bloco Olodum inspires an adulation so intense that “entertainment” seems a wholly inadequate term. Even “joy” somehow falls short. On stage or off, behind cordas or lining the sidewalks, smiles, affection and appreciation are the order of the day. Throughout the decades and around the world, performing artists – those worthy of the name – have always fostered a rapport with their audience that transcends the purely transactional. Olodum sets a standard of community engagement that few have been able to emulate, let alone achieve.

There is no denying that they are performers. Since 1979, they have issued some 20 recordings and given concerts around the globe. In the English-speaking world, Olodum’s profile received a boost when they played on The Rhythm of The Saints, Paul Simon’s follow-up to his groundbreaking Graceland album. Six years later, they provided the pulse for Michael Jackson’s “They Don’t Care About Us”; the video was directed by Spike Lee. More recently they joined Jennifer Lopez, MPB star Claudia Leitte and the Rapper Pitbull for “We Are One (Ole Ola)”, the official anthem of the 2014 FIFA World Cup. Olodum were invited to participate after complaints that an earlier version did not sufficient recognize the musical heritage of the host nation.

Such achievements are certainly a source of pride, but it is what happens in Salvador that ensures Olodum’s place in the hearts of locals. While the ensemble includes a core of songwriters, singers and instrumentalists, they are supported by a battery of drummers. Playing with Olodum is a rite of passage for many young Bahians, a percussive apprenticeship that fosters discipline and empowerment.

The “samba reggae” sensibility of Olodum and kindred groups has helped to revitalize the historical center of Salvador’s upper city. Today visitors find it a lively warren of bars and restaurants, laid-back cafes, shops, and galleries. For all these amenities the place retains an authentically residential feel. This is a change from prior decades, when the colonial streets of Brazil’s first capital were given over to cycles of violence, poverty and despair. The topography of the neighborhood speaks of an even more savage past.

Flanked by the City Museum and the SENAC culinary school, the Largo do Pelourinho is a triangular plaza which by extension gives its name to the surrounding area. Yet pelourinho is Portuguese for “pillory” and for generations the largo was the site of a whipping post where rebellious slaves were publicly flogged.

That such a gruesome locale is now an epicenter for ecstasy may seem contradictory. Nevertheless, it is impossible to examine Carnival without confronting slavery. In medieval Europe, the celebration brought a measure of joy to the masses suffering under feudal conditions. It should come as no surprise that in the New World, those lands with the most vibrant pre- Lenten traditions remain those most deeply scarred by the transatlantic trade in labor and lives.

Such a fascinating read

What a coincidence, I just listened to The Rhythm of the Saints on my drive to the Pine Barrens.