**************

In recent months, we’ve examined fictional portrayals of Carnival in Trinidad and New Orleans. We’ll close out the series - and 2023 - with a visit to Brazil.

****************

Jorge Amado’s 1966 novel Dona Flor and Her Two Husbands chronicles a love triangle. Those involved? First and foremost, there’s our title character, the kindly, talented proprietress of a cooking school. Her husband Teodoro is a mild-mannered pharmacist, devoted to his wife and playing the bassoon. Finally, there’s the ghost of Flor’s first husband: a gambler, a philanderer, and all-around bon vivant.

So far, such a plot might seem typical of magical realism, a literary genre characteristic of many Latin American countries. However, the very first sentence of the opening chapter places the action definitively in Brazil:

Vadinho, Dona Flor’s first husband died one Sunday of Carnival, in the morning when, dressed up like a Bahian woman, he was dancing the samba, with the greatest enthusiasm, in the Dois de Julho Square, not far from his house.

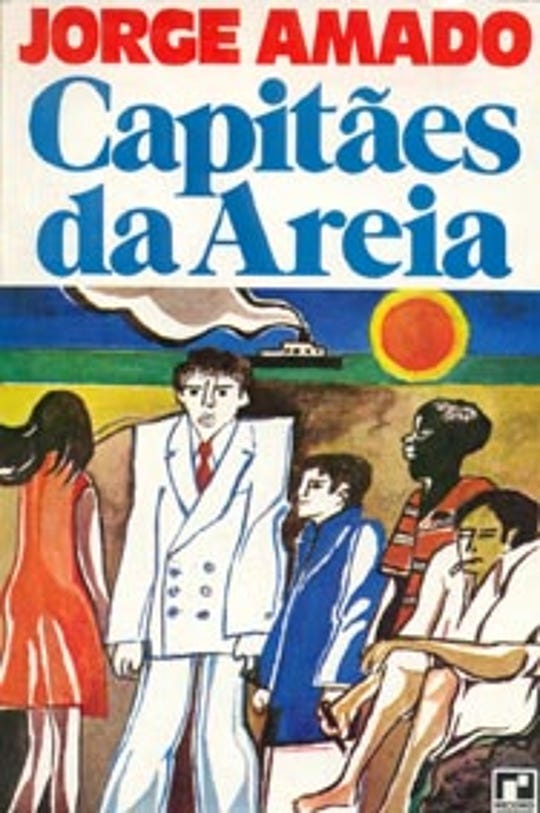

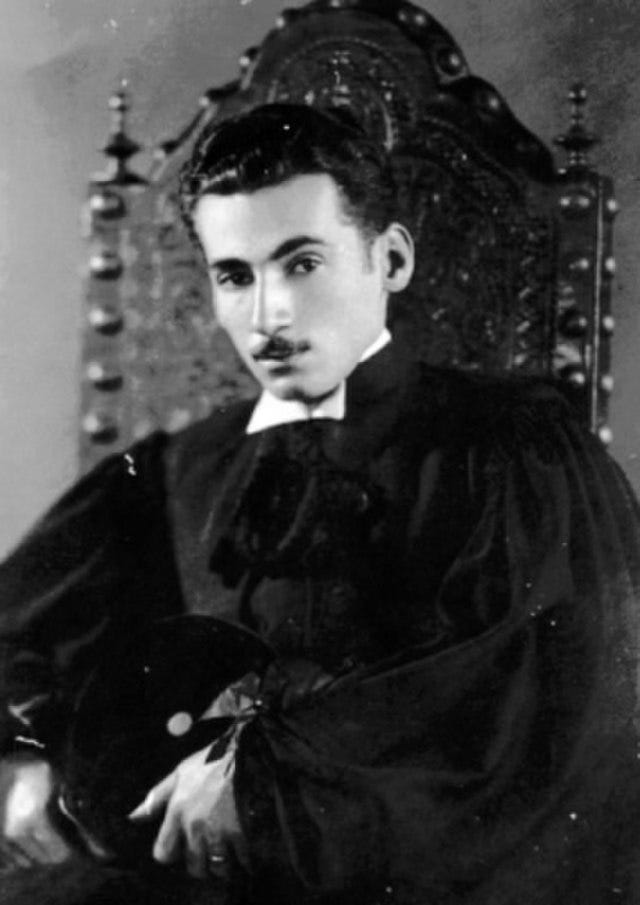

Adapted for the screen in 1976, Dona Flor is certainly Amado’s most famous book, but is not the most representative. His earlier works focus on social themes – greed, inequality, and the brutality borne of desperation. Captains of The Sands, published when the author was just 25, follows the adventures and misadventures of a gang of thieving orphans who live in an abandoned warehouse by the docks in Salvador da Bahia. The Violent Land has a setting that is more rural, detailing the chocolate boom in the humid interior of the state. Vicious “cacao colonels” stop at nothing to exploit their laborers and grab land from their competitors.

These youthful novels call to mind the naturalism of Emile Zola or Theodore Dreiser, and reveal the influence of Marxism. Amado’s involvement with leftist politics meant he was frequently exiled from Brazil. In 1951, the Soviet government awarded him the Stalin Peace Prize – a distinction also bestowed on Chilean poet Pablo Neruda and the American singer Paul Robeson. But Amado’s fiction is seldom dogmatic. Vibrant portrayals of his state and its people are never subsumed by ideology. His sympathetic views on religion – Catholicism and Afro-Brazilian rites – also diverged from Communist party lines.

In later years the author’s style became more comic. He never abandoned political concerns, however. Indeed, his critique of Brazil’s class system was all the more powerful for being wrapped in satire. 1958’s Gabriela, Clove and Cinnamon also revealed a knack for strong, complex female characters, at odds with stereotypical machismo.

The various threads of Amado’s career culminate, superbly, in Dona Flor and Her Two Husbands. A proper appreciation of that masterpiece is beyond the scope of this issue. Let’s make do with one more excerpt, a few pages from our first:

It was Carnival Sunday, and who did not have an automobile parade in which to participate that night, a celebration in which at which to amuse himself into the early hours of the morning? Nevertheless, and in spite of all this, Vadinho’s wake was a success, an “outstanding success” as Dona Norma proudly pronounced and proclaimed…The employees of the mortuary were in a hurry, their work increased by Carnival. While others were amusing themselves, they had their hands full with the dead, the victims of accidents and fights.

Like so much great literature, the passage reminds us that exhilaration is often mingled with grief. Since we can seldom anticipate the latter, we must always strive to embrace the former while we can.