In the United States, the most vibrant celebrations can be found in Mobile, New Orleans, and other communities along the Gulf Coast. Several hundred miles to the south, one can find the epicenter of the Carnival tradition in Mexico.

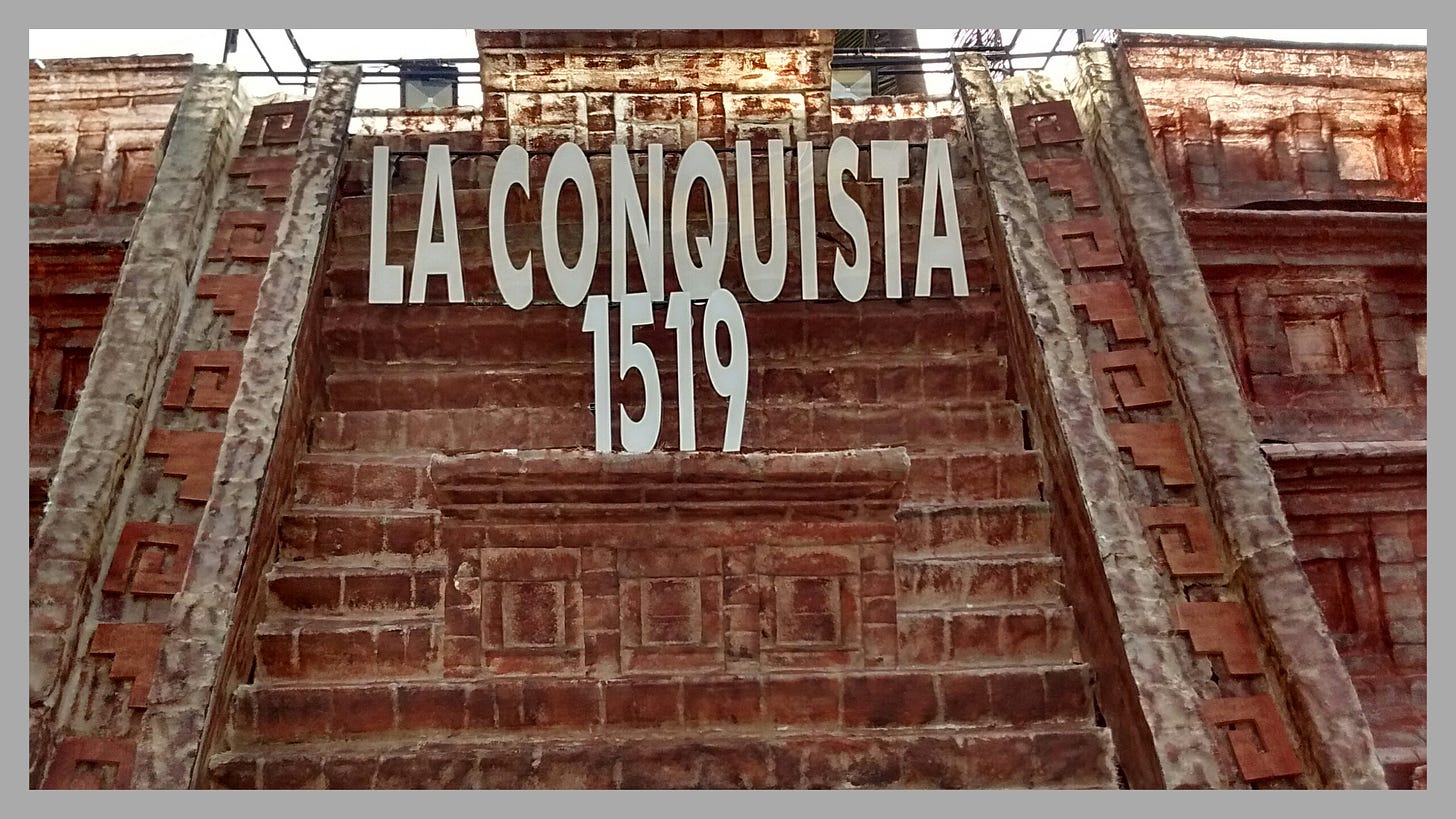

Christopher Columbus went to his grave publicly insisting that he had discovered a western route to the Indies. It did not take Spanish explorers in the Caribbean long to realize they were actually near the shores of two massive continents, neither of which was Asia. Exploitation of the mainland’s riches began in earnest on Good Friday, 1519. That’s when the notorious conquistador Hernan Cortez established a foothold on San Juan de Ulua, an island in the harbor of what would be become the city of Veracruz.

The Europeans had firearms and cavalry – both unknown in Mexico at the time. Despite these advantages, their conquest of such a vast country would not have been possible if Cortez had not been careful to cultivate alliances with local peoples. Today, a symbolic link to Aztec culture is a key element of cultural identity across Mexico. But this was hardly the case 500 years ago.

After deliberately scuttling his ships, Cortez and his indigenous allies marched on Tenochtitlan, the capital of the Aztec empire. Employing treachery and force of arms, they vanquished the forces loyal to the emperor Moctezuma. Heading south, Cortez torched the city now known as Cuernavaca. Ordering his men to tear down a sacred pyramid, he used the stones to construct a fortified palace that still stands to this day. In 1529, King Carlos I rewarded Cortez’s brutality with a royal title – Marques del Valle de Oaxaca – and a fiefdom covering a wide swath of central Mexico.

Tenochtitlan was renamed Mexico City and became the capital of The Viceroyalty of New Spain. At its greatest extent, the territory included a huge chunk of North and Central America, many Pacific and Caribbean Islands, and the northeast coast of South America. Veracruz remained a crucial Spanish port, where plundered wealth and commodities were shipped back to Iberia. With the famous “Cry of Dolores” Mexicans declared their independence on the 16th of September, 1810. The Spaniards, of course, were reluctant to let such a rich possession go without a fight. In the 10-year war that ensued, Veracruz was violently contested.

In 1838, the port was bombarded by French forces during the so-called “Pastry War”. In 1847, American forces commanded by General Winfield Scott killed hundreds of Mexican civilians before capturing the city. Another gringo incursion, ordered by President Woodrow Wilson in 1914, was resisted by cadets from Mexico’s naval academy, located nearby. This history has inspired the sobriquet “Heroic Veracruz” – and a Warren Zevon classic:

In the 21st century, Veracruz has retained its strategic and commercial importance, but has also become a popular vacation destination. While it may not have the international cachet of Acapulco, Cancun, or Los Cabos, it attracts visitors from all over Mexico – especially in the days leading up to Lent.

The sultry, sticky climate has nurtured a laid-back attitude in the part of the Jarochos, as natives proudly call themselves. Music permeates the city’s life. This is especially true in the Zocalo, or central plaza. Ringed with palm trees, and graced with the dome of its 18th-century cathedral, it’s a magical place to while away the hours of a tropical evening. Wandering marimba ensembles play for patrons of the many historic cafes, vibrant bars and gracious hotels. Open-air danzon balls take place throughout the year. During Carnival, these performances are supplemented by concerts featuring pulsing ranchera, reggaeton hits, and the wistful ballads known as corridos. Even those who know nothing of the city, will recognize son jarocho – the Jarocho Sound -- most famously embodied in “La Bamba”.

Beloved as this musical heritage is, the Brazilian approach to Carnival has also made its mark in Veracruz. During the festive season, a number of homegrown samba schools take to the streets. Running down from the historic center and the gritty docklands, the Malecon is a scenic boulevard. To the south, communities like Playa Mocombo and Boca del Rio host beach clubs, high-rise hotels and trendy restaurants. Parades roll back and forth along this route, casting searchlights across the sky and shooting lasers over the waters of the Gulf.

With the notable exception of Venice, parade floats are a common fixture of Carnival processions around the world. Known as carros alegoricos in Spanish, they serve as literal advertising vehicles, while their design and construction help drive local economies.

Between parades, floats can be found parked along side streets and alleys. Without their riders, lights and sounds, they can seem like forlorn harbingers of Ash Wednesday. Such somber reflections are forgotten once Tuesday’s first cerveza is served, the marching bands tune up, and the balloons are inflated one last time.

Thank you for this history lesson, especially of Veracruz!