One of history’s great strategists, Gaius Julius Caesar subjugated the Celtic peoples of Gaul, attacked Britain, and vanquished domestic rivals to become the final, absolute ruler of the Roman republic. He was less successful against Germanic tribes. The emperors who reigned in his wake won territory and lost it in turn, but for the most part modern Germany consists of lands that escaped Roman control. To Caesar, Germans were barbarians posing a threat to civilization. Indeed, invasions by the Ostrogoths, Vandals, and Visigoths hastened Rome’s collapse in the 5th century AD. Yet between the empire’s founding and its fall, a sort of détente developed, and German mercenaries came to make up a large part of the imperial army.

The bishops of Rome succeeded where her legions often failed. By the Middle Ages the Germans were all at least nominally Catholic, and Teutonic knights were instrumental in Christianizing Scandinavia and the Baltic countries. Martin Luther was a priest in Wittenberg when he wrote his 95 Theses, condemning Church practices such as the sale of indulgences – the absolution of sin in exchange for monetary donations. The upheaval released by the Reformation was especially brutal in central Europe. Dukes, princes and other potentates used doctrinal differences to enlarge their holdings. Germany remained an almost feudal patchwork of states until 1871, long after unified nations had emerged elsewhere on the continent.

Today, Catholics account for some 30% of the Federal Republic’s population, mainly in the south and west. The German church has no greater monument than Cologne’s immense and stunning Dom, or cathedral. Started in 1248, it remains the most visited site in Germany – an impressive feat when one considers the throngs that descend on Munich for Oktoberfest.

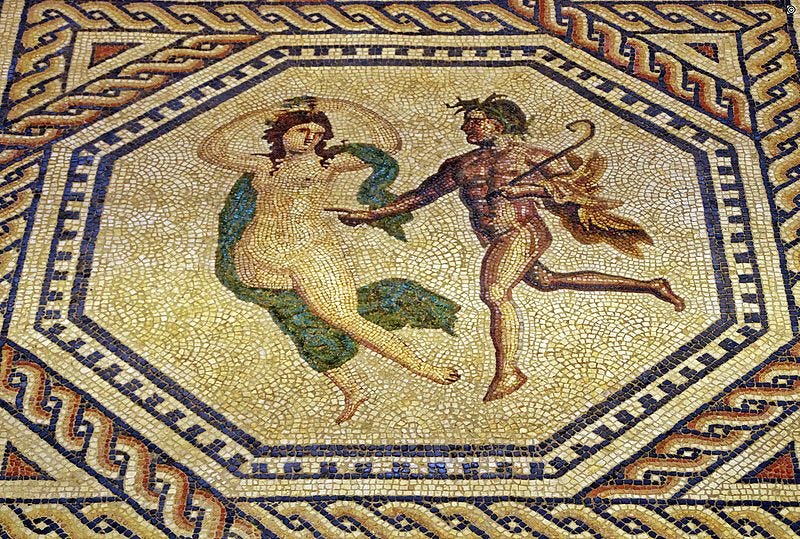

Colonia Claudia Ara Agrippinensium was established in the year 50 as a Roman outpost on the Rhine River. The cathedral and its twin spires came through World War II more or less intact, yet Cologne occupies part of Germany’s industrial heart and was subject to heavy Allied bombing. In 1941, the construction of an air-raid shelter uncovered the ruins of a 3rd-century villa; the location is now the site of the city’s fascinating Romano-Germanic Museum.

The museum’s centerpiece is a well- preserved mosaic depicting scenes from the mythic life of Dionysos. Appropriate enough, given that Cologne hosts what many consider the most vibrant bacchanal in the German-speaking world. The festivities are overseen by His Craziness, the Carnival prince. He is attended by the Bauer, a loyal peasant character and the Jungfrau. The latter can be translated as “maiden” or “virgin” and, true to the spirit of the celebration, has historically been portrayed by a man. Rounding out the retinue, the members of the Prinzengarde make an utter mockery of military discipline.

The first written reference to the proceedings dates from 1341. So entrenched is the tradition that, despite its subversive nature, it was tolerated under the Nazis, with one key exception. The Jungfrau in drag proved somehow too depraved for the party of Goering and Himmler, which mandated an actual female maiden. When the “Thousand Year Reich” ended after twelve, the Carnival court was restored in all its transgressive glory.

Streets resound with spontaneous shouts of “Alaaf!” and the cadences of Buttenrede, a form of rhyming, humorous rhetoric. “Butten” means a cask or keg, such containers typically serving as a lectern for the orators. Der Wieberfastnacht, or Women’s Carnival, falls on the last Thursday before Lent; local Damen are free to kiss all the men they desire. Less pleasantly, leave is given to snip the tie off any Herr foolhardy enough to wear one. As in other places, merriment rages until Ash Wednesday, but the highlight is Rose Monday, when rowdy processions abound. The main parade in Cologne attracts over a million spectators and is broadcast on national television.

In the Rhineland, the celebration tends to be known by the Latinate term Karneval. In Bavaria, the Germanic Fasching or Fastnacht prevails. Regardless of nomenclature, Carnival is considered the funfte Jahreszeit, or “Fifth Season of the Year”, officially commencing at 11 AM on the 11th of November. Elsewhere, the time and date are associated with the armistice that ended the First World War. Given the horrors that subsequently sprang from that defeat, it is understandable that Germans cherish the more joyous implications of the day.

It will be noted that the Karneval season encompasses the entire period of Advent, Christmas and New Year’s. The persistence of the custom suggests a longing basic to the primeval essence of Europe. Since long before the birth of Christ, before the rise of Greco-Roman society, there has been an impulse to spread cheer and color even – especially – during the darkest months.

Fascinating read and yet another reason for a long overdue visit!

I had no idea that they celebrated Carnaval in Köln! I'll have to visit for it. It's a lovely city. I've been to the top of the Dom. That sounds kinky...