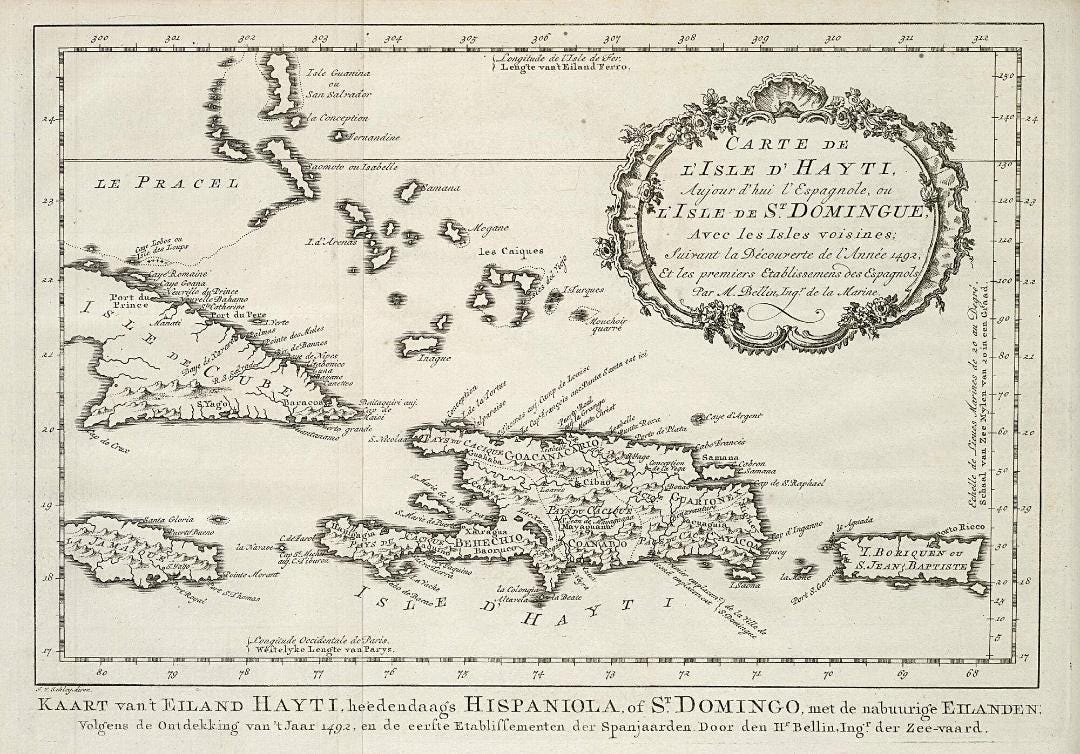

Today, Haiti is the poorest nation in the Western hemisphere, but in the 1780s “The Pearl of the Antilles” produced some 40% of the world’s sugar. An enviable position for the French crown and wealthy planters, far less so for the miserable people who actually harvested and processed the addictive sweetener. Cane quickly depletes nutrients from the soil where it is grown, and bringing the crop to market is extremely labor intensive. In the mercantile era, profitability depended upon the Triangular Trade. Enslaved Africans were packed into ships; those who survived the passage were forced to work the fields under horrifying conditions. They produced sugar and its byproduct, rum. These commodities were shipped to cities in New England or Europe; profits were used to purchase manufactured goods. Exported to Africa, the items were traded for more slaves.

It was a system as lucrative as it was diabolical. Yet despite colonial riches, the French economy was in shambles. Food shortages and widespread discontent gave way to outright revolt. After the execution of Louis XVI, the constitution of 1795 banned slavery, outraging landowners and alarming the newly independent Americans, who feared the implications for their own plantation economy.

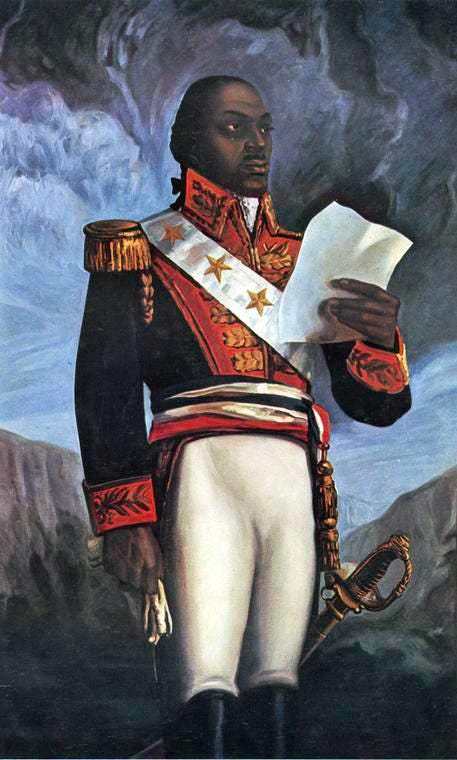

Egalitarian rhetoric proved hollow in 1802, when the ascendant Napoleon dispatched General Charles LeClerc to restore slavery. The Bonapartist forces managed to arrest Toussaint Louverture, a “free man of color” who had led an insurrection in 1791 despite remaining loyal to the ideals of republican France. Louverture died in prison, but his lieutenant Jean-Jacques Dessalines stunned the world, defeating the invaders and declaring Haiti an Independent republic.

The Haitian Revolution is lauded as the only truly successful uprising of enslaved people in history. The world’s oldest Black republic, the country inspired national liberation movements around the globe. Yet France did not accept the sovereignty of its breakaway colony until 1825. Recognition was contingent on payment of 150 million gold francs as “reparations”. Although this was later reduced to 90 million, the debt and its associated fees strained the Haitian treasury for over a hundred years, being finally paid off in 1947. (In the USA, hostility of the southern states kept Washington from acknowledging the government in Port-au-Prince until 1862. American marines also occupied the country from 1915 until 1934.)

Foreign affairs aside, Haiti has seen an inordinate degree of domestic strife. From the start, there were tensions between the liberated slaves and gens du couleur libres, some of whom had held their fellow citoyens in bondage. Military coups and violent repression have been perennial. The regime of Francois “Papa Doc” Duvalier is the most notorious example. Bolstered by the Tontons Macoute, a force of paramilitary thugs, Duvalier declared himself president for life in 1964. In 1971 power passed to his son Jean Claude, whose own reign was only marginally less brutal.

Democratization has proceeded by fits and starts since “Baby Doc” was exiled in 1986. In early 2010, the country was devastated by a 7.0 magnitude earthquake. At least 100,000 people were killed. The 280,000 buildings that were destroyed or severely damaged included the National Palace: an almost too-perfect symbol of freedom’s disappointed promise. One might assume that Haiti’s people, who continue to be wracked by hunger and economic misfortune, would have neither the strength nor the will for frivolity. Anyone making such an assumption really doesn’t understand Carnival — or Haitians.

French continues to be an official language in Haiti, alongside Kreyol, or Haitian Creole. Roman Catholicism, another colonial legacy, remains the dominant religion. Protestant churches have grown significantly in recent years, yet Catholics – roughly 55% of the population – outnumber Baptists (the next largest denomination) by a factor of three. The CIA’s World Fact Book reports that as of 2018 only 2% of Haitians identify themselves as adherents of Vodou. However, that same source notes that “many Haitians practice Voodoo (sic) in addition to another religion”. This is surely a massive understatement by the good folks in Langley.

Regardless of what they may tell census officials or sociologists, Vodou is part of the heritage shared by all Haitians. On the night of 14 August 1791, escaped slaves and free Blacks gathered at Bois Caiman for the sacrifice of a pig. The ritual is seen as the catalyst for the revolt that led to independence. Linguistically and theologically Vodou is linked to the Voodoo traditions of Louisiana and the Vodon rite practiced in Benin, Togo, and other parts of West Africa. Devotees recognize Bondye (from the French Bon Dieu) as the supreme being of the universe.

Bondye is viewed as a remote deity, unknowable to mortals. The faithful rely on the intercession of the Loa, subservient spirits who control most aspects of earthly life. The Loa are divided into families; revered figures include Papa Legba, Damballa, and Maman Brigitte. Said to have a fondness for rum laced with hot peppers, Brigitte is the wife of Baron Samedi – Loa of the dead and head of the Guelde family. The Baron shares his wife’s taste for strong liquor, along with fine cigars. With a skull-like face, he is often depicted in a top hat and dark purple suit.

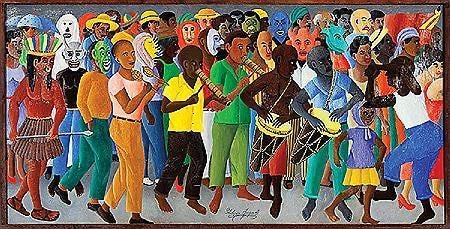

Given to debauchery and obscene utterances, Baron Samedi certainly comes across as a carnivalesque figure. Drumming, dancing, and spiritual ecstasies are all aspects of Vodou worship. Nevertheless, it would be wrong to view the street parties in Port-au-Prince and Jacmel as Vodou rituals per se. Popular festivals all over the world reflect the wider social context, and Haiti’s pre-Lent throwdown is no exception.

Political instability has hampered most sectors of the local economy, yet Haiti boasts a strong and vibrant music industry. Few bands enjoy a greater reputation than Boukman Eksperyans. They take their name from Dutty Boukman, a Vodou cleric who (along with priestess Cecile Fatiman) presided over the ceremony at Bois Caiman; the “Eksperyans” part is an homage to Jimi Hendrix.

The group rose to prominence during the 1990 Carnival season. The song Ke M Pa Sote (“I’m Not Afraid”) was heard as a protest against the military government that held power after the fall of the Duvalier dictatorship. Vodou Adjae, their debut album, was nominated for a Grammy, even as the band made powerful enemies. When president Bertrand Aristide was overthrown in a coup d’etat, Boukman Eksperyans went into exile. Returning to Haiti in 1994, they have been a fixture of Kanaval ever since.

Alongside similar acts, they are seen as proponents of mizik rasin, or “roots music”. The genre remains popular, though in recent years younger people have embraced konpa. Also known as compas, this is a slick idiom marked by vibrato-heavy electronic grooves.

At the opposite end of the spectrum, rara music is propelled by tubular single-note trumpets, traditionally crafted from bamboo. To an extent, these wind instruments seem akin to South African vuvuzela, or the didgeridoos played by aboriginal Australians. The syncopated percussion that accompanies them may evoke the frevo of northeastern Brazil, but rara remains decidedly, uniquely, Haitian. Rara processions are most common between Ash Wednesday and Easter, rather than Carnival season proper. Even this fact testifies to the richly syncretic nature of the republic’s culture.

Recurring turmoil back home has created a vast Haitian diaspora. Expatriates and their children have built vital communities all around south Florida, Quebec, and New York. The cycle of political gains and reverses has fostered a two-way flow of people and musical influences.

The rapper Wyclef Jean was born in 1969 at Croix-des-Bouquets. At the age of twelve, he and his family migrated to Brooklyn before settling in New Jersey. As part on the groundbreaking act The Fugees, he achieved international recognition in the early nineties. His 1997 solo debut was titled Wyclef Jean presents THE CARNIVAL featuring Refugee Allstars.

A sprawling masterpiece, The Carnival extended the boundaries of contemporary hip-hop. In addition to his former bandmates, Wyclef collaborated with artists as diverse as the Neville Brothers and Celia Cruz, the Cuban-American salsa queen. Subsequent volumes of the epic were released in 2007 and 2017. He also dropped an EP titled J’ouvert, a nod to Trinidad’s annual bacchanal. The Carnival Tour, Wyclef Jean’s first extending outing in a decade, kicked off in early 2018.

Caribbean accents are less pronounced in the music of Arcade Fire, a Canadian ensemble. Regine Chassagne, a singer and multi-instrumentalist, was born outside Montreal in 1976; her parents moved there during the regime of “Papa Doc” Duvalier. At first listen, her band’s music evokes Germanic synth pop and British art rock far more than anything coming out of the tropics. Yet Chassagne’s ancestry has been a constant influence, especially with the 2013 release of Reflektor.

The pulsing rhythm of rara occasionally emerges from the album’s rich arrangements. Kanaval’s presence is a matter more of ideas than notes and chords. Win Butler, Chassagne’s husband and bandmate told Rolling Stone that:

Going to Haiti for the first time with Regine was the beginning of a major change on the way I thought of the world…there’s sex and death and people dressed up as slaves with black motor oil all over their faces and chains, and there’s little kids in puffer fish outfits or dressed like Coke bottles. There’s fire-breathing dragons that shoot real fire at the crowd.

Elsewhere in the interview, Butler extols the transcendent “feeling of less of a break between the spirit and the body”.

The konpa artist Michel Martelly, who performs as Sweet Micky, was born in 1961 and moved to Miami in 1984. He married Sophia Saint-Remy in 1987, and for many years the couple owned homes in Palm Beach. Releasing dozens of albums over the decades, Martelly was wildly popular, despite some controversial opinions. He is widely seen as an apologist for dictators. While others have drawn inspiration from Vodou, Martelly has derided the faith as “black magic” and “bullshit”.

Such stances did not appreciably diminish his following. In January of 1996, he received a message that “The city of Port-au-Prince keenly desires your participation in the upcoming Carnival festivities”. The letter was signed by Manno Charlemagne, the mayor of the capital and a former musician himself.

Martelly appeared before the assembled revelers in a pink wig, a bra, and panties. The undergarments were, to quote the journalist Elise Ackerman, “amply padded to produce the desired curvaceous effect”. The float where he was performing soon approached a reviewing stand by the National Palace. The singer took the opportunity to berate President Rene Preval: “You are only there for five years. I am here forever because I am in the streets!”

Fifteen years later, during the first post-earthquake election, Sweet Micky was chosen as the 41st president of Haiti. He held that position until 2016, then resumed his musical career without missing a beat.

******************

“MARDI GRAS” painting by Salnave Philippe-Auguste (1908-1989)

All other images in public domain.

Fascinating!

Thank you for the music and history!