This month’s newsletter drops on the final day of Hallowtide, a three-day period observed by some Christians since the 8th century. The triduum commences on October 31st, or All Hallow’s Eve. According to The Catholic Encyclopedia November 1st is set aside “to honour all the saints, known and unknown”. November 2nd – All Souls’ Day – is also called The Commemoration of All The Faithful Departed.

The period coincides with Samhain, a harvest festival long celebrated by Celtic peoples in Britain and Ireland. Traditionally, burial mounds were opened – a practice that clearly shaped the modern secular Halloween. Centuries later, the blending of Spanish Catholicism and indigenous Mexican customs manifested itself with Día de Muertos, or Day of The Dead. Both holidays can be considered examples of religious and cultural syncretism.

There is a sense in which Carnival can also be called syncretistic. Its timing is derived from the liturgical calendar, but has never been a recognized part of Church doctrine. The celebration emerged in late medieval Europe, but incorporates elements of much older traditions. In this issue and the next, we’ll examine two ancient deities whose worship seems to have anticipated the pre-Lenten party that is enjoyed by so many around the world.

It is a commonplace to assert that the devotion to saints, so intrinsic to Catholic belief, represents a remnant of paganism. Such an accommodation is said to have helped The Church attract adherents for whom the strict monotheism of the Old Testament was bewildering or inadequate. This interpretation is rejected by devout Catholics, who consider the scriptures to be divine revelations and Church law to be promulgated by infallible pontiffs. Even aside from the objections of the faithful, the view of sainthood outlined above is, at best, simplistic.

The emperor Constantine, in the 4th century, declared that Christianity was to be the official religion of the Roman state. This conversion is often understood as something like a software upgrade – out with Minerva, Venus and Mars; in with The Father, The Son, and the Holy Ghost. Yet even before the crucifixion and the apostolic missions of Peter and Paul, the spiritual make-up of the Greco-Roman world was both volatile and complex.

In The Cults of the Roman Empire Robert Turcan provides a fascinating glimpse into the cosmological ferment of the ancient Mediterranean. A professor at the Sorbonne, Turcan argues that Rome’s expansion from republican city-state to multi-ethnic empire fostered a competitive marketplace for theological ideas. In this analysis, Christianity was but one of several “oriental” faiths vying for the allegiance of Roman citizens and their subject peoples.

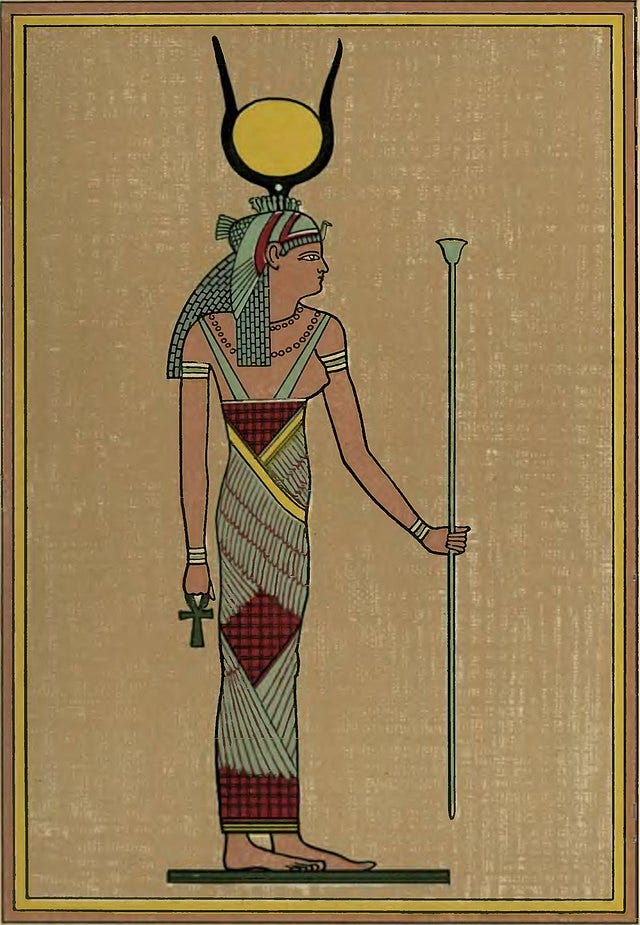

Isis, originally a goddess of Egypt, generated particular reverence. The conquests of Alexander the Great helped establish Greek language and philosophy throughout much of the Middle East and North Africa. Yet the process of imperialism is never a straightforward matter of military dominance. Alexander’s general Ptolemy established a capital in the Nile delta; he and his successors adopted many of the customs of the much older Egyptian civilization. Alexandria was a port city, and the cult of Isis was already widespread by the time of Mark Antony’s dalliance with Cleopatra, the last of the Ptolemaic monarchs.

Each year on March 5th, devotees gathered for the Festival of Isis’ Vessel, commemorating a voyage the goddess made in search of her murdered husband, the god Osiris. Intriguingly, Turcan calls the observance “a kind of carnival”. Indeed, in his most famous work, the Latin novelist Apuleius describes a scene that seems familiar today.

The Golden Ass is a satiric fantasy, depicting the accidental transformation of Lucius, a curious young man, into a beast of burden. Yet the tale’s magical elements exist alongside an almost journalistic sense of social conditions. Apuleius was himself a devotee of Isis; at one point his narrator derides a Christian character for rejecting “all true religion in favour of a fantastic and blasphemous cult of an ‘Only God’” It is safe, therefore, to assume his depiction of the Isisian mysteries is more or less creditable.

At the heart of the procession is a “great band of men and women of all classes and ages”— the initiates of the cult. They are joined by others, representing various walks of life: a philosopher and a fisherman, a gladiator and a judge. Yet Apuleius makes it clear that these are costumes --- for all its spiritual import, the scene is a “playful masquerade”. Each celebrant is decked out according to his votive fancy; one man, in a silken gown, strolls “with a woman’s mincing gait”. This sartorial subversion is not limited to the human realm— there is a she-bear arrayed as a wealthy matron, and an ape wearing a straw hat with a saffron robe.

The spectacle is illuminated by lanterns, candles and torches. Then as now, no parade is complete without its beat:

Next came the musicians, interweaving in sweetest measures the notes of pipe and flute; and then a supple choir of chosen youths, clad in snow-white holiday tunics, came singing a delightful song which an expert poet (by the grace of the Muses) had composed for music, and which explained the antique origins of this day….

Isis was embraced by many Romans, but she was ultimately a foreign deity. By contrast, the gods and goddesses of ancient Greece can be considered be part of the traditional religion of Rome. For the most part, the Romans used different names, but the stories and attributes of their gods and heroes mirrored those of Mount Olympus. Among these was the wine god Dionysos, known in Rome as Bacchus.

We’ll raise a glass to that gentleman – and see out the year – next month.

I wear a Palladium wedding band because of my fondness for Pallas Athena. But the great god Pan still holds sway.

So interesting! Looking forward to Part 2!