On January 6th of this year, Carnival season in New Orleans kicked off with a parade organized by the Krewe of Joan of Arc. The next day, up the river in Baton Rouge, Republican Jeff Landry was sworn in as the 57th governor of Louisiana. Neither event was remarkable in itself. But the juxtaposition highlights some truths about the Crescent City, The Pelican State, and American history.

Before his election, Landry served as Louisiana’s Attorney General. In that capacity he frequently clashed with John Bel Edwards, his two-term Democratic predecessor. Like other right-wing officials across the south and Midwest, Landry campaigned on a platform hostile to big cities and their inhabitants. New Orleans and its port are key the state’s prosperity, but Landry’s rhetoric often casts it as territory to be subjugated by force.

The New Orleans Police Department has been subject to a consent decree since 2013. That’s when federal investigators found patterns of misconduct violating constitutional rights. Landry has called the decree “a pernicious threat to federalism”. Restricting stop-and-frisk tactics, in his view, fostered “hug-a-thug” policies – a bigoted dog whistle so blatant a deaf cat could hear it.

An aversion to federal oversight doesn’t mean the governor wants municipalities to manage their own affairs. In an era of climate change, he has threatened to withhold flood protection funding to compel adherence to the GOP’s radical social agenda. “In Louisiana, we have one of the most powerful executive departments in the country” he told Tucker Carlson on Fox News. The previous governor, he lamented, didn’t take advantage “to bend that city to his will…but we will”.

Landry’s disdain for his state’s largest city is, ironically, echoed by the way some New Orleanians talk about their hometown’s most famous thoroughfare. Of course, this is rarely grounded in outright hatred, and there is much to dislike about Bourbon Street, even for those of us who love the French Quarter. Multiple generic daiquiri stands, correlated with vomit-splattered sidewalks. Souvenir shops overflowing with Voodoo-themed schlock. And then there are the hordes of tourists (young and not-so-young) for whom the Vieux Carré is but an alternative to spring break in Daytona. These elements grow increasingly annoying as Fat Tuesday approaches. Ritual exhibitionism spikes to the extent that, topless or not, passersby are in constant danger from plastic necklaces hurled from on high.

Mardi Gras has been observed along the Gulf Coast since 1699. However, Big Easy natives are quick to point out the “beads for boobs” economy – so iconic for so many – is a relatively recent innovation. They also explain that the frat party vibes quickly diminish once the big parades roll beyond Canal Street. In residential neighborhoods, folks gather for intergenerational celebrations where extra slices of king cake might be considered the height of sensual indulgence.

Both these considerations are true enough as they go. Yet there is a caveat to bear in mind. In a country as large and diverse as the United States, “good clean fun” will ever be a relative and malleable concept.

Since long before Lady Marmalade started teaching horny adolescents their first French sentence, New Orleans has had a reputation for vice. In part this is due to the Anglo-Saxon tendency to project their own thwarted desires upon their Gallic neighbors. But there is evidence that at least some French authorities worried about lax morality in their subtropical colony.

A visiting priest once expressed his concerns to Antoine de la Mothe, sieur de Cadillac. That honorable magistrate is said to have replied “If I send away all these loose females, there will be no women here at all, and this would not suit the views of the king, or the inclinations of the people”.

Napoleon’s sale of the Louisiana territory did little to dispel the salacious stereotypes. One legacy of the colonial era was that New Orleans had a larger community of free Blacks (Gens de couleur libre) than other southern cities. But the export of commodities like sugar and cotton relied on enslaved workers. When the American Civil War broke out in 1861, New Orleans was the largest population center in the Confederacy. Union forces quickly recaptured the area. Following the Emancipation Proclamation and Reconstruction, tourism became increasingly important.

Toward the end of the century, a coalition of civic reformers and economic interests established Storyville, an officially sanctioned red-light district centered around Basin Street. Drunkenness and prostitution can never be eliminated, went the logic, so it is best to confine such commerce to a discrete area. If certain madams, landlords and politicians happened to get rich in the process…well, that was simply the price of reform.

Visitors consulted Blue Books – annual directories of the various establishments. There were descriptions of individual sex workers and their specialties. Neighborhood pharmacies advertised quick cures for the various ailments endemic to the “Sporting Life”. Tugboat pilots and dockhands might patronize dimly lit one-room “cribs”. Wealthy businessmen from Chicago or Dallas spent their time and money at upscale bordellos featuring live music, ornately carved furnishings and fine works of art. One of the most celebrated was Mahogany Hall, owned and operated by Lulu White. Her surname notwithstanding, the Alabama native made much about her status as an exotic “Octoroon”

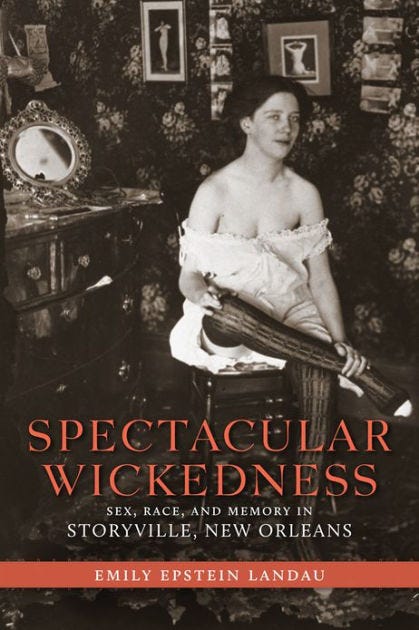

Spectacular Wickedness by Emily Epstein Landau presents a detailed, fascinating history of Storyville. She points out that the ordinance establishing the district went into effect in 1897 – one year after the Supreme Court’s notorious ruling in Plessy v. Ferguson. That case established that strict segregation of railways and other public facilities was constitutional. Ironically, the lure of interracial sex was a continuous draw for white men visiting New Orleans. That fact contributed to the shuttering of Storyville, some 20 years after it was established.

In April of 1917, President Woodrow Wilson asked Congress to declare war on Germany. The Germans, allied with the Ottoman and Austro-Hungarian empires, had been fighting the British and French for three years at that point. Ostensibly, a clampdown on prostitution bolstered military preparedness by reducing the spread of venereal disease among the new recruits. The actions of Wilson’s administration also reflected his personal prejudices.

Historians often describe the 28th president as a progressive, but that was certainly not the case in terms of race relations. As a student at Johns Hopkins University, he befriended future novelist Thomas Dixon. Dixon’s fiction romanticized the Ku Klux Klan and inspired Birth of a Nation. Wilson arranged to have the film shown at The White House. The idea of soldiers and sailors socializing with African-Americans in dancehalls and barrelhouses offended his segregationist sensibility.

The closing of the district serves as the frame around New Orleans, a movie musical starring Louis Armstrong and Billie Holiday. Although the action takes place during the First World War, the film was released shortly after World War Two. Viewers at the time would have recognized parallels to the pogroms that occurred before and during the latter conflict, and mass displacements which followed in its wake.

Like Bourbon Street today, Storyville catered to debauched fantasies around the clock and throughout the year. Nevertheless, the arrival of Carnival revealed opportunities to “kick it up a notch”, to adopt a dash of Emerilian phraseology.

Since the 18th century, the wealthiest and most aristocratic Creole families marked the final days before Lent with fancy dress balls. These were invitation-only affairs; 100 years after Louisiana’s statehood, prominent Anglos often found themselves snubbed. Old-line krewes like Comus and Rex were formed, in part, as a response to this exclusion. Empresarios in Storyville took things further, advertising “French balls” in honor of the season. The galas were open to any white man with the price of admission. It is safe to bet that the entertainment on offer was not limited to quadrilles, waltzes and pâtisserie.

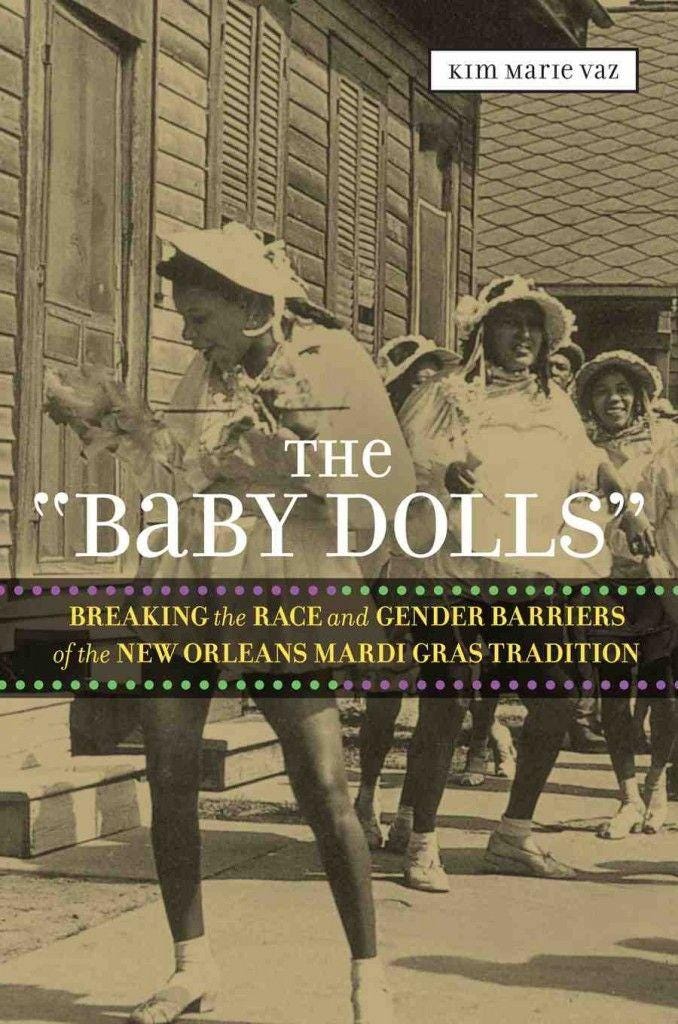

The Back O’ Town neighborhood, sometimes called Black Storyville, is the focus of The “Baby Dolls” a 2013 study written by Kim Marie Vaz, a professor at Xavier University. Like Big Chiefs and their attendant Spy Boys, Baby Dolls on parade manifest the Black masking traditions of New Orleans. However, the origins of Mardi Gras Indians are somewhat obscure. By contrast, Vaz identifies 1912 as the year Beatrice Hill, Leola Tate, and Althea Brown first stepped out under the name of The Million Dollar Baby Dolls. In their abbreviated costumes, in daylight hours, they amused spectators with the type of gyrations generally reserved for paying customers in dimly lit parlors and saloons.

Since that time, various groups have introduced variants on the theme, but the basics have remained for more than a hundred years. These include very short skirts, often with colorful trim and elaborately curled tresses worn under fanciful bonnets. The most obvious point of reference might be the actress Shirley Temple, but the similarities only go so far. Temple’s fame reached its zenith the early 1930’s. Americans, reeling from the Great Depression saw in Temple’s childish charm reflections of a national innocence which never truly existed. The Baby Dolls were very much adults, and frequented parts of the Mississippi where the Good Ship Lollipop never dropped anchor.

In subsequent decades, the Baby Doll look was adopted by other groups of female revelers, many of whom took pains to distance themselves from any connection with commercial sex. From the perspective of the 21st century, Baby Doll masking may seem of a piece with the amateur burlesque scene typical of many cities, or the pole dancing classes sometimes offered at fitness clubs. A tad risqué to be sure, but ultimately bourgeois and respectable.

Professor Vaz does not quibble in stating that the processions of the Million Dollar Baby Dolls were marked by:

Traditional Creole songs and blues, turning tricks, drinking, smoking reefers and “starting and causing” street fights complete with brick throwing and razor flashing. The name they adopted for themselves, “Baby Dolls” was based on what their pimps called them.

The milieu that gave birth to Baby Dolls was one rife with abuse and back street abortions, gonorrhea and addiction. To Vaz, however, those early maskers were “united in entrepreneurial sisterhood”; despite privation “They carved out a niche of empowerment”.

Such a thesis will surely fuel debate in the groves of academe and beyond. In any event, the persistence of the tradition tells us something important about Mardi Gras. The Pre-Lenten jubilee is rarely the anarchic orgy its detractors claim. But it has never been as chaste as certain revisionists would like us to believe.

Thanks for a great piece of prescient history!

wow.. that was so detailed and fascinating.. I have always wanted to see the Carnival here..