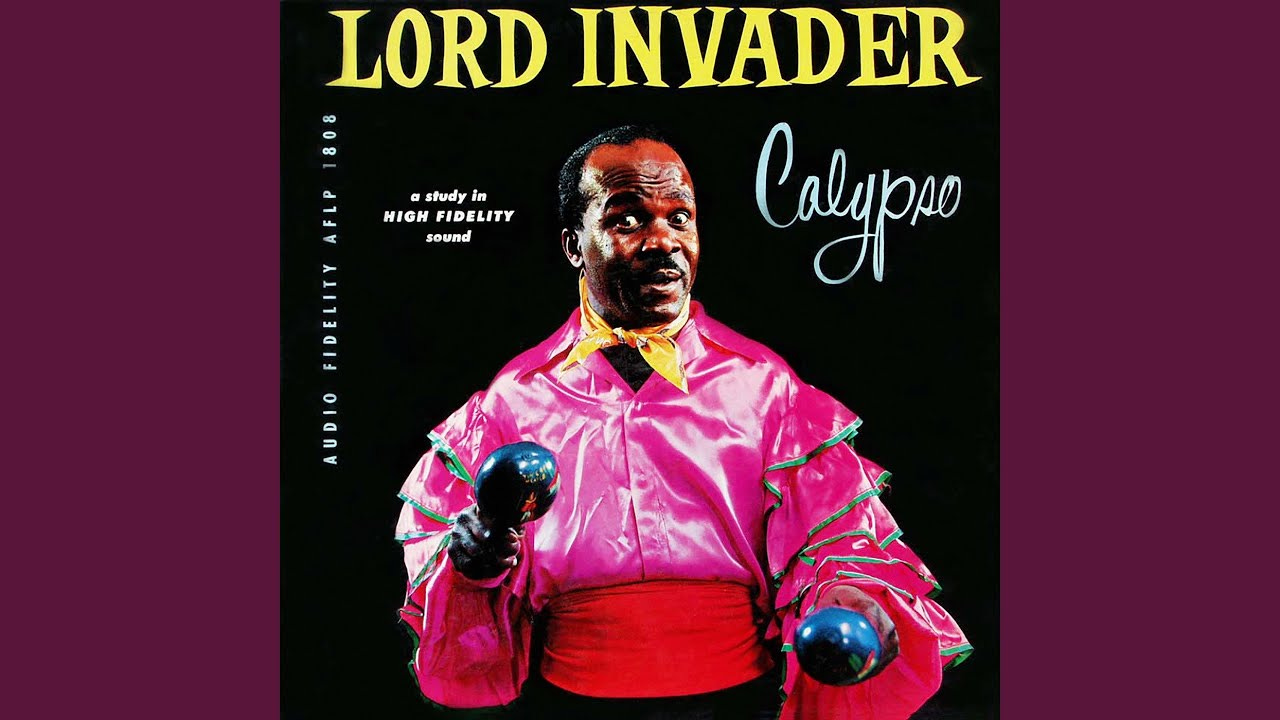

In 1943, as Trinidad’s Carnival season was heating up, Rupert Grant, who performed as Lord Invader, released a calypso called “Rum & Coca-Cola”. Musical competitions with cash prizes for top singers had been a feature of the island’s celebration for decades. Political commentary and sexual innuendo – just subtle enough to escape colonial censors – were always popular. Invader’s composition incorporated both.

World War II brought enormous changes to the West Indies. Trinidad remained a British possession, but the “Destroyers For Bases” agreement introduced a large US military presence. Building and maintaining those bases put money into the pockets of many local men. But American soldiers and sailors, who did not have to budget for food and shelter, had a distinct advantage when it came to rest and recreation.

Superficially, “Rum & Coca-Cola” may seem no more than a catchy paean to a sweet fizzy cocktail. But those whose romantic prospects were stymied heard an eloquent protest against a situation that found

… Mother and Daughter

Working for the Yankee Dollar…

The tune was so successful that it could still be heard in November, long after the end of Carnival. That is when Morey Amsterdam (who would later appear on the Dick Van Dyke Show) arrived in Port of Spain for a USO show. In 1944 The Andrews Sisters, a Greek-American trio recorded a single called “Rum & Coca-Cola”. The melody was nearly identical to Invader’s song; the themes were similar, but songwriting credit was attributed to Morey Amsterdam.

After the war, local impresario Mohammed Khan, Lord Invader, and attorney Emil Ellis took action against Amsterdam in US district court. Along with the testimony of servicemen who had been stationed in Trinidad, Ellis introduced a souvenir booklet containing the original lyrics – or at least, those that could be printed without provoking obscenity charges. The defendants had clearly underestimated the importance of Carnival and the visibility of its rituals to the Trinbagonian public.

The weight of evidence convinced Judge Mortimer Byers to rule in favor of the plaintiffs. No penalty was assessed, however. The parties reached a settlement whereby Lord Invader received an undisclosed amount of cash and Amsterdam purchased the copyright to “Rum and Coca-Cola”, allowing him to perpetuate the fiction that a comic from Illinois had somehow written one of the most famous calypsos of all time.

Amsterdam’s actions were sleazy and exploitative. They were also part and parcel of a recording industry that regularly profited by ripping off Black musicians. In 21st century terms, the episode might be described as cultural appropriation. But that is problematic, for a couple of reasons.

The Andrew Sister’s ersatz rendition jumpstarted a postwar calypso boom in the United States. At least some Americans developed a taste for the genuine item. Many calypsonians who led hand-to-mouth lives back home secured high-paying gigs in New York and elsewhere. Doubtless these Caribbean artists found much to resent in the entrenched racism of the era. Reaching a wider audience, however, is unlikely to have irked them.

Secondly, we should recall that “appropriate” is both a verb and an adjective. In the first sense (per The American Heritage Dictionary of The English Language) it can mean “to take possession of or make use of exclusively for oneself, often without permission”. As an adjective, it denotes “suitable for a particular person, condition, occasion, or place”. During Carnival, behavior that would otherwise be deemed inappropriate has long been tolerated, expected, and welcomed.

Of the 100 stories that make up Giovanni Boccaccio’s Decameron only one is set in Venice. The tale of Friar Alberto, a lecherous cleric, includes this passage:

"Today we are holding a carnival, to which everyone has to bring a partner wearing some form of disguise, so that one man will be dressed up as a bear, another as a savage, and so on and so forth."

The excerpt highlights a basic truth about Carnival: dressing up, playing a role, has been part of the proceedings from the beginning. Whether Trick-or-Treating through suburbia, stumbling around city squares, or dancing a quadrille under glittering chandeliers, we love our disguises. However, the forms we choose are seldom realistic depictions of The Other. More often, they are projections of thwarted desires, unresolved fears, secret hopes. Masquerades, by definition, are unreal. But that fact makes them no less fascinating.

It must also be noted that The Decameron was written in 1348, before the era of European colonialism. In Boccaccio’s day, the word “savage” did not have the racial connotations it would later acquire. Derived from the Latin word for forest, it evoked The Wild Man of The Woods, a folkloric figure. Soon enough, the Columbus’ voyages would usher in an era of suffering for millions in Africa, Asia and the Americas. The stereotype would then be repurposed to justify the brutality of the conquerors.

By the time the United States was founded, “savage” had definitively become a pejorative. After a century of bloodshed, forced expulsions, and broken treaties, the Stars and Stripes flew over both coasts. White Americans, secure in the supremacy their “civilization” had inflicted on native peoples, recast their victims as Noble Savages. This cynical trope has since been used to hawk everything from butter and motor vehicles to sports franchises and shoes.

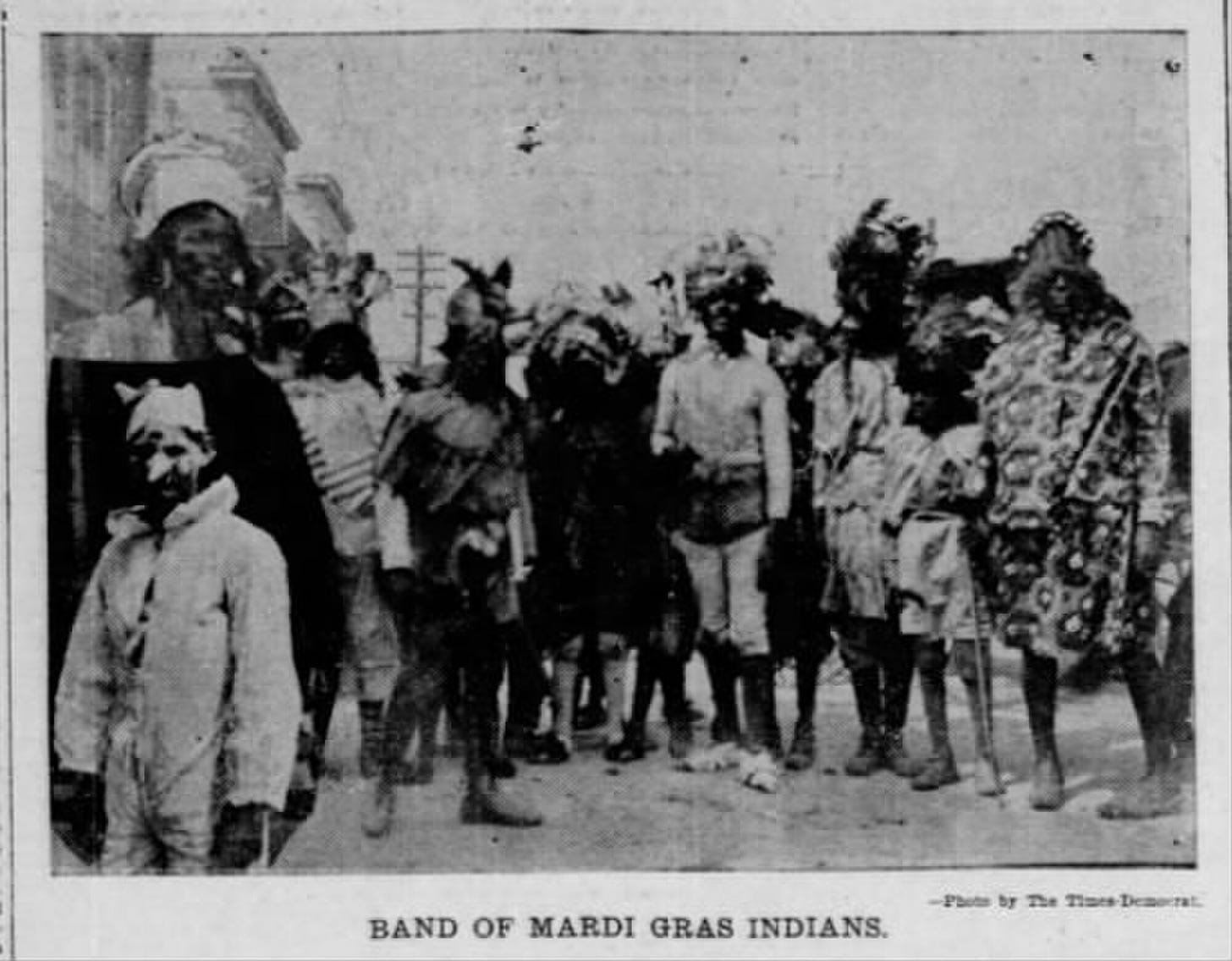

The career of William Cody epitomized this shifting attitude. Better known as Buffalo Bill, the former soldier organized “Wild West” shows that toured the eastern states and Europe. Along with trick riders and sharpshooters, Cody employed members of the same tribes he had previously tried to eradicate. The winter of 1884-85 found the troupe in New Orleans. That coincides with the emergence of the city’s famed Mardi Gras Indians – Black masking groups who step out on Fat Tuesday, St. Joseph’s Night, and Super Sunday at the end of March.

Indigenous peoples have lived along the Gulf Coast for millennia. Currently, Louisiana is home for 15 tribes recognized at the state or federal level. But the regalia sported by Black “Indians” calls to mind the Lakota Sioux and other nations of the Great Plains. Academic ideologues may view the phenomenon as cultural appropriation, or a forerunner of cosplay. Both interpretations, however, neglect crucial historic context.

Buffalo Bill’s sojourn in The Crescent City occurred eight years after the Battle of Little Big Horn, where native warriors vanquished General George Custer and the 7th Cavalry; the massacre at Wounded Knee was still to come. Meanwhile, the collapse of reconstruction meant southern Blacks, emancipated in 1863, were effectively stripped of legal protections. Those who asserted their constitutional rights risked arbitrary prosecution and KKK terrorism.

It is easy to see why African-Americans would embrace the ideal of resistance to white hegemony. Carnival fostered alternate modes of masculinity, creativity, and dignity. Solidarity with other oppressed people, half a continent away, was more symbolic than logistical – but symbols have real power. 150 years later, Mardi Gras Indian traditions are authentic expressions of local identity.

Big Easy anthems like “Iko-Iko” “Indian Red” and “Hey Pocky Way” originated in the chants of Black maskers. The Wild Tchoupitoulas, Yellow Pocahontas, and Creole Wild West are particularly well known, but there have been dozens of “tribes” over the years, often associated with particular neighborhoods or extended families. Of course, in all communities, grudges and tensions exist. In the past, the stylized taunting of other groups sometimes gave way to outright violence and a settling of scores. The celebrated “Spy Boy” would scout ahead while the rest of the entourage made their way through the streets.

Things are considerably more peaceful these days. When two groups encounter each other, there is still a degree of rhythmic boasting to the beat of tambourines and rattles. There is also deep and abiding respect. Top accolades go the Big Chief whose hand-sewn suit, created anew each year, is deemed to be “The Prettiest”.

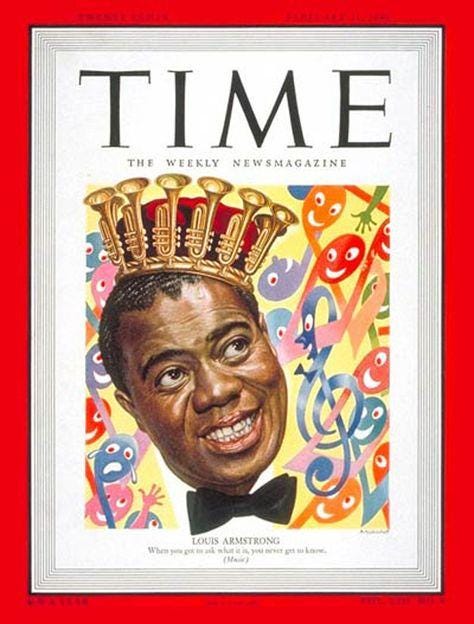

In 1949 Louis Armstrong presided over the Mardi Gras parade organized by the Zulu Social Aid & Pleasure club. By that time “Satchmo” was a wealthy man. He’d already appeared in a dozen motion pictures, sang or played on countless records, and was beloved by jazz fans around the world. For the native New Orleanian, being elected the Zulu King was the fulfillment of a “Life-long dream”.

Zulu first rolled in 1916, when old-line krewes like Rex were closed to non-white citizens. The parade was permitted, but masks were forbidden. Members responded by donning grass skirts and black face paint. Notably, the majority of Africans enslaved in the new world were taken from the western edge of the mother continent. Their descendants in New Orleans have few genealogical links to the Zulus of southern and eastern lands. Whites performing in blackface were an all-too-common fixture of minstrel shows at the time. Black men doing so presented a grotesque parody of a parody.

Zulu’s use of blackface to blunt the impact of hateful stereotypes is part of a long tradition. During the Revolutionary War, British officers derided American forces as mere “Yankee doodles”. Soldiers fighting under George Washington embraced the epithet. In the wake of Stonewall, the slur “queer” was joyfully and defiantly reclaimed by the LGBT population. But as the civil rights movement gained strength, clichés from the vaudeville stage seemed incompatible with the vision of Malcolm X, Martin Luther King, and other leaders. This critique, however, overlooked the many community initiatives supported by Zulu and other social aid groups. Membership – less than two dozen in the 1960s – has since rebounded. Zulu’s signature painted coconuts are now among the most prized of all parade throws.

Jarring though they may be when first seen, similar practices can also be found among Afro-Caribbean revelers in Colombia, the Dominican Republic and elsewhere. Despite its unique heritage, Louisiana is part of the United States, and it is in that setting that its Carnival must be discussed. When Black professionals paint their faces on St. Charles Avenue, it has a qualitatively different meaning than white frat boys doing the same thing in Baton Rouge. To pretend otherwise is to indulge in a vile and malicious sophistry.

The western hemisphere’s first Carnival was observed as early as 1520 by Spanish colonists on Hispaniola. Trinidad was also a Spanish possession, just off the South American coast. Finding it difficult to attract settlers from Spain, and wary of the Protestant English, authorities issued the Cedula de Poblacion, inviting French planters to the island.

In addition to a shared Catholicism, Frenchmen and Spaniards both relied on a workforce of enslaved Africans. So it was that a European celebration was enriched by customs of the Igbo, Yoruba, and others. Finally capturing the colony in 1797, the British attempted to dampen the festivities, to little avail. After slavery was abolished, South Asians – both Hindu and Muslim- also contributed to the diversity of modern Trinidad & Tobago

These elements created a Carnival tradition as vibrant as any in the world. Such is its appeal that other English-speaking Islands have used T&T as a template when introducing bacchanals of their own. St. Vincent & The Grenadine, Bermuda, and St. Lucia are recent examples. These newer festivities typically take place in the summer months, and so are delinked from the organic tradition of pre-Lent debauchery. Older Trinidadian rituals – Dame Lorraine skits, kaiso, and stick-fighting - are inconspicuous or absent. Social media has fostered an almost exclusive emphasis on J’ouvert, profit-driven Mas bands and, especially, soca.

Jamaica has played an enormous role in musical history. However, Carnival celebrations did not begin there until the 1990s. At some events, local DJs may mix in dancehall and hip-hop tracks. This amounts to heresy for purists who insist that soca, and only soca, should be heard at fetes. The self-appointed gatekeepers of “Caribbean Carnival” present something of a paradox. Firstly, the phrase tends to be used in a way that excludes countries outside the Anglosphere. Even within this myopic definition, there is at least a tacit recognition of Trinbagonian origins. “Cultural appropriation is fine” they seem to say, “Just make sure to appropriate it MY way.”

Such a characterization is, of course, overly simplistic. It is unfair, almost absurd. But let’s take it a little further.

Carnival began in late medieval Europe, its timing determined by the ecclesiastical calendar. Even then, as travel guides and tourism authorities remind us ad nauseam, there were echoes of earlier traditions: The Roman Saturnalia, Dionysian rites, the cult of Isis. Were Europeans therefore appropriating the culture of their own pagan ancestors? When Constantine made Christianity religion of his empire, was he appropriating the scriptural patrimony of Israel and Judah?

Indeed, many scholars believe that, as practiced at the time of Christ, Judaism had integrated aspects of Persian cosmology. When discussing faith “syncretism” rather than appropriation has been the preferred nomenclature. A case can be made that all religions are syncretic to some extent.

From the earliest days, humans everywhere have adopted recipes, musical ideas, and clothing from their neighbors. New technologies have accelerated processes that previously took generations. Discourse about cultural appropriation reflects anxieties about the pace of change, and perpetuates notions of a “pure” ethnicity which, in fact, has never existed.

When appreciating the dazzling tapestry of Carnival, we should always acknowledge, respect, and uplift the original strands. When designing or wearing a costume, we should be cognizant of how easily imitation can degenerate into mockery. At the same time, excessive diligence about appropriation should never blind us to the beauty of living, breathing, and evolving culture.

Amen, from one historian to another!

Great piece. Love the way you thread together all the connections