In our October issue, we discussed the Dominican Republic, where colonizers from Spain staged the New World’s first Carnival in the 16th century. Along with firearms, slavery and smallpox, the Spanish and Portuguese introduced a range of Iberian folkways. To this day, communities across the peninsula continue to host processions and fiestas throughout the year. Religion and raucousness are frequently intertwined. In Seville, Holy Week rituals are particularly striking. A few weeks later, that Andalusian city celebrates the Feria de Abril. Each summer since 1945, the town of Buñol has attracted visitors eager to participate in a massive food fight with tomatoes. Then there is the Festival of San Fermin, marked by the famous running of the bulls through the streets of Pamplona.

San Fermin takes place in July, and has no direct relation to Lent or Carnival. Yet in “The Sun Also Rises” Ernest Hemingway employed his characteristic Anglo-Saxon understatement to convey a decidedly Latin type of exuberance:

The fiesta was really started. It kept up day and night for seven days. The dancing kept up, the drinking kept up, the noise went on. The things that happened could only have happened during a fiesta. Everything became quite unreal finally and it seemed as though nothing could have any consequences. It seemed out of place to think of consequences during the fiesta.

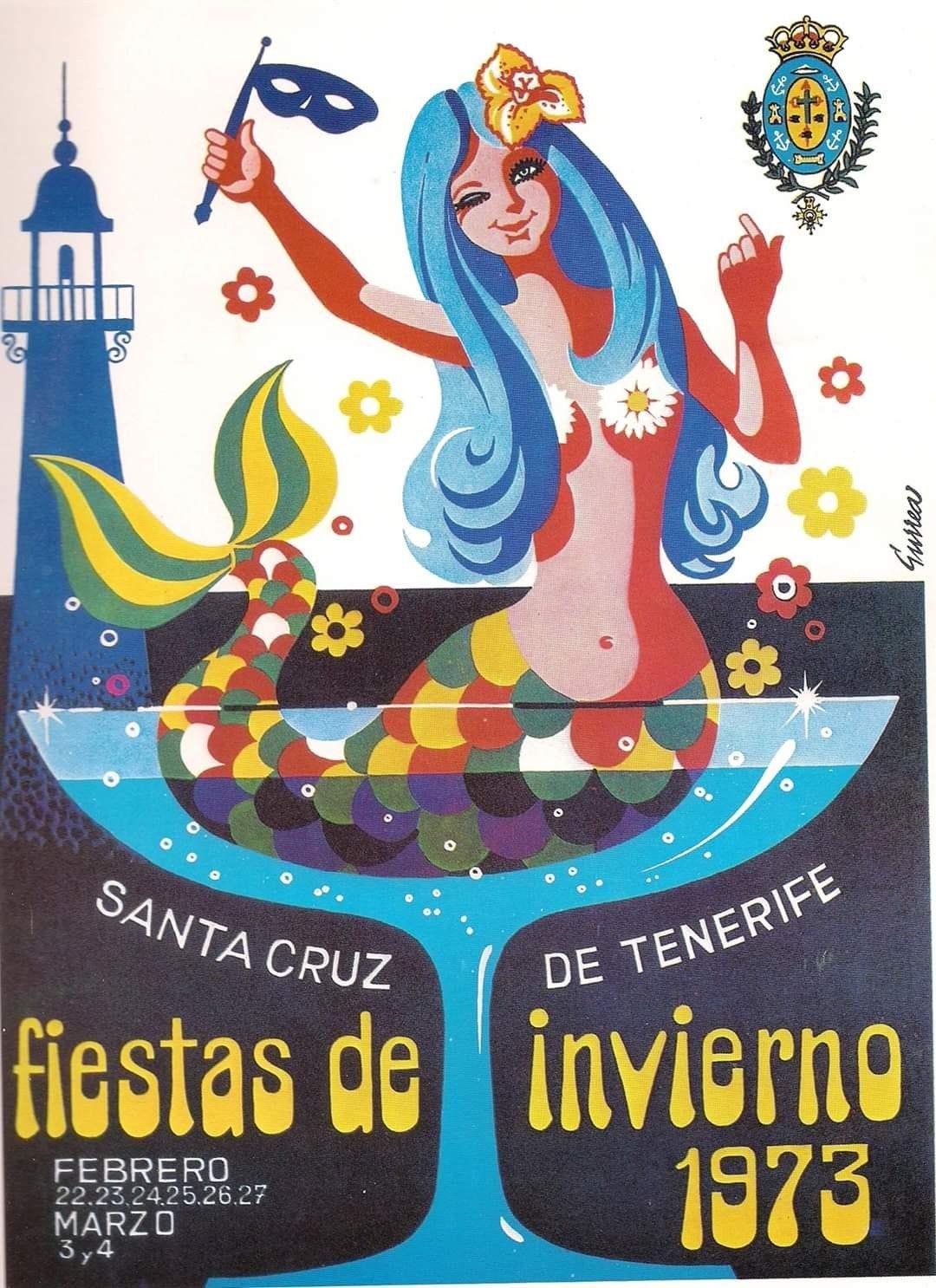

Carnival proper is observed all over Spain. Many argue the country’s best bacchanals take place, not in Madrid or Barcelona, but in the Canary Islands. Gran Canaria is home to the Playa de Canteras, a golden stretch of sand lined with welcoming cafes and beachfront paella joints. Most of the Carnival action, however, takes place in and around the park of Santa Catalina. Elaborate stages are erected each year to host a program of performances and costume competitions. Those wishing for a somewhat more subdued festival may turn the village of Arrecife on Lanzarote.

Revelers of such a bent would do well to avoid the island of Tenerife, often considered to host the most debauched celebration in Spain – a bold claim when one considers the things that happen on Ibiza. There is hedonism, to be sure, but also a strong element of satire, with political and religious figures viciously lampooned.

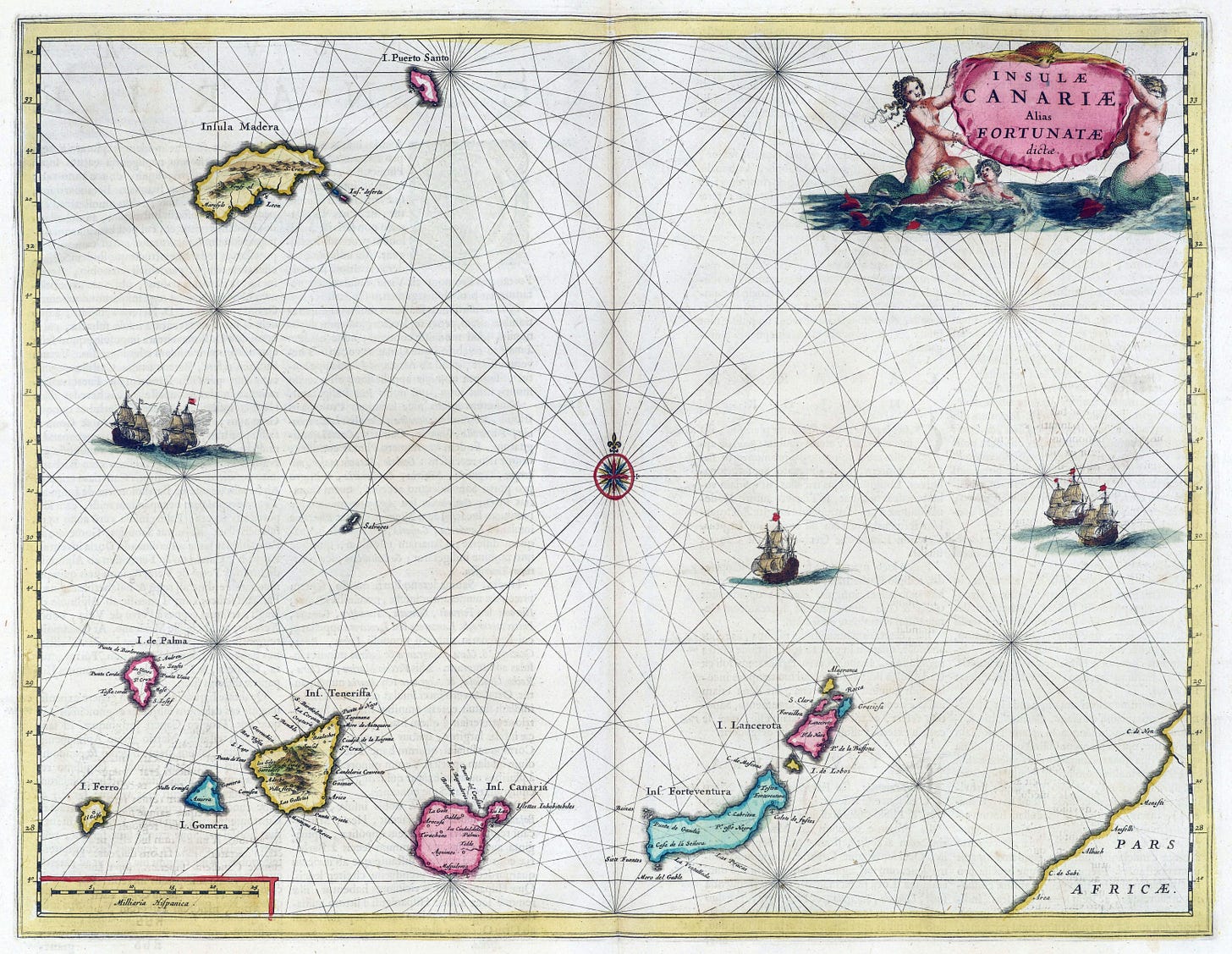

People living in the islands have the same rights and responsibilities as those on the mainland. In some ways, the situation parallels that of Hawaii, another volcanic archipelago. Yet Honolulu is approximately 4800 miles from Washington, DC. By contrast the Canaries are situated a few hundred miles out in the Atlantic, off the coast of Morocco and the Western Sahara.

Despite this relatively proximity, the islands were long isolated from the currents of western and Islamic civilization. Thought related to the Berbers of North Africa, the indigenous Guanche tribes led an almost Neolithic existence based on hunting, herding and the cultivation of a few subsistence crops. While the Romans seem to have been vaguely aware of the islands, there is no record of European contact until 1312, when the Genoese seafarer Lanzarotto Malocello landed on what is now called Lanzarote. Systematic conquest began some 90 years later.

The chain can be viewed as the western limit of the Old World, or the beginning of the new. Subsequent exploration would upset the balance of power in Europe and bring immeasurable torments to the peoples of the Americas. By the 1930s, las Canarias would themselves be embroiled in events that unleashed cataclysmic misery in Iberia and beyond.

The Spanish-American War left the United States in control of Puerto Rico, Guam, and the Philippines. Cuba emerged as an independent nation. Coupled with the earlier loss of Latin American colonies, the conflict effectively ended Spain’s run as an imperial power. The humiliation of the defeat exacerbated social divisions. King Alfonso XIII was only 12 years old when hostilities ended in 1898. In 1923, he gave his support to a military coup led by Miguel Primo De Rivera. As Prime Minister, De Rivera lauded the values of “Country, Religion and Monarchy”, but such slogans could not forestall the growing unrest of workers or discontent among the Basque and Catalan minorities. De Rivera retired to Paris and died in 1930. The following year Alfonso himself fled to Rome, although he did not formally abdicate.

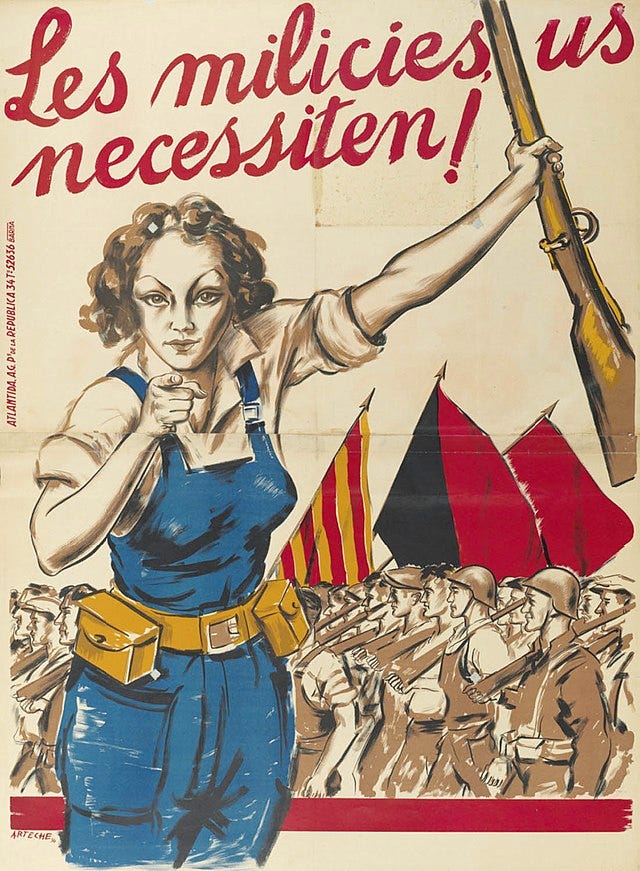

The republic declared in 1931 was the most left-leaning in Western Europe. Bourgeois liberals governed with – and struggled against – coalitions of communists, anarchists, and trade unions. Radical measures alarmed traditional landowners and the armed forces, especially after Francisco Franco, a reactionary general, was transferred to the Canary Islands in early 1936. This “banishment” by the government did not have the desired effect. In June, a secret meeting of officers took place in a forest on Tenerife. By summer’s end the Generalissimo commanded an army of “Nationalist” rebels, and the Spanish Civil War had begun.

International volunteers rushed to defend the republic, which was also supported by the USSR. Yet the Nationalists, backed by Nazi Germany and Mussolini’s Italy, prevailed. Assuming the title of Caudillo, or leader, Franco ruled until his death decades later. The civil war has been called the dress rehearsal for World War II, though Spain remained neutral during that wider conflagration.

Franco was certainly a right-wing autocrat, though some scholars debate whether it is strictly accurate to call him a fascist. Such distinctions would hardly matter to those tortured or killed under his regime. Up to half a million died in his campaign to take power, with a further 100,000 disappearing or perishing in the years that followed. Repression of the Basque language and culture gave rise to the ETA organization, which has killed hundreds in terrorist attacks. Catholic notions of patriarchy informed the legal framework; as late as the 1970s Spanish women could not open bank accounts without their husbands or fathers as co-signors.

In the face of such atrocities, the prohibition of drunken processions would seem of little import. Though the rituals of flamenco and bullfighting were upheld as essential emblems of national pride, the old tradition of Carnaval was banned during the era of Franquismo. Such a measure may seem strange when Getulio Vargas was manipulating Rio’s Carnival traditions, and even the Nazis put up with the celebrations in Cologne. The Spanish edicts have been explained as matter of public safety. In the wake of civil war, masks and costumes might have enabled acts of revenge or sabotage, hindering consolidation of the regime. Yet the facts of Franco’s life suggest a more personal antipathy.

The English historian Paul Preston wrote what is widely considered the definitive biography of the generalissimo. The work naturally focuses on military and political developments, but family life is given its due. The Francos hailed from Galicia, a cool and rainy region in Iberia’s northwest corner. While climate and character are two different things, Franco is said to have exhibited an icy reserve far removed from the torrid temperament of Mediterranean clichés. In this, his resembled his mother Pilar, a woman of pious seriousness. By contrast, his father Nicolas had a fondness for late night card games and extramarital affairs.

When Francisco was 15, the elder Franco essentially abandoned his wife and children. There was no divorce, but Nicolas moved to Madrid with his mistress Augustin Aldana; the two lived together for 35 years. While his two brothers seem to have inherited their father’s licentious spirit, the future dictator cultivated what Preston calls an “extreme propriety”. At one point he listed among his Great Patriotic Achievements the elimination of venereal disease at the military academy in Zaragoza. Ruthless and intolerant with his enemies, Franco did not womanize, drank wine only in moderation at meals, and sought to project an aura of “exemplary austerity” -- the very opposite of carnivalesque indulgence.

Even today, El Caudillo has his defenders and apologists. La Rambla de Santa Cruz, a main drag on Tenerife, was officially called the Rambla de General Franco into the 21st century, and many still use the street’s old name. Without speculating on the depth of pro- or anti-fascist sentiment in the archipelago, there was one sphere in which the Canaries were decidedly subversive.

When the celebration was forbidden elsewhere, the annual party was re-designated as The Winter Festival. In the weeks before Ash Wednesday, bands still marched and vino flowed. Franco finally died in 1975. With the restoration of constitutional monarchy under Juan Carlos I, Carnival was ready to roll – as sloppy, loud, and blasphemous as ever.

Despite vast differences in technology and military prowess, the Guanches put up fierce resistance to the 15th century conquistadores. It took almost 100 years to the completely subdue the Canarian natives. The rigors of the fight seem have left the Spaniards with little energy for naming their new settlements. To this day, geographic indicators can be a source of some confusion.

Its name notwithstanding, Gran Canaria is not the largest island of the chain, although its capital – Las Palmas – is the largest city, (and the seventh largest in Spain). This should not be mistaken for La Palma, an island some 200 miles to the west. The chief municipality there is Santa Cruz de La Palma; there is also a Santa Cruz on Tenerife – which actually is the largest of the islands. Complicating matters, Puerto de la Cruz refers not to the port of Santa Cruz but to a separate town on the other side of Tenerife. So it is that Carnival in the Canaries can leave visitors befuddled long before the first cork is pulled.

In Santa Cruz de La Palma, the frenzy peaks on Carnival Monday, locally known as the Fiesta de los Indianos. Stylized garb evoking Native Americans is a feature of many celebrations around the world. Yet in this case the “Indians” in question are locals who sailed off to the Spanish Caribbean, a/k/a The Indies. Those who prospered often returned sporting colonial fashions which struck their old neighbors as ridiculous. In a parody of migratory affectation, Palmeros don all-white clothing and Panama hats. Those who lack such accoutrements nevertheless attain a bleached look by the day’s end: Carnival Monday erupts in a battle royale with talcum tossed by the fistful at all and sundry.

One figure escapes the powdery melee. La Negra Tomasa is a grotesque caricature of an Afro-Cuban matron. She arrives in blackface and a print dress garish enough to distract – at least for a while – from a certain underlying masculinity. The portrayal of Tomasa is neither politically or ethnographically correct. Islanders, however, deny any malice in the tradition. “We are all so in love with La Negra Tomasa” writes the journalist David Sanz, arguing that adults look forward to the fiesta with the impatience of their children awaiting the arrival of The Three Kings on the feast of Epiphany. There does indeed seem to be a sincere appreciation for Cuban culture, if one is to judge by the all the mojitos consumed and rumba beats pounded out on conga drums. The Canaries are simultaneously European and African. For one day at least, one island also becomes a spiritual part of Havana.

The population of Santa Cruz de Tenerife is more than 10 times that of its namesake on La Palma. It is here that one encounters the critical mass for a street party as vibrant and well-lubricated as any in the European Union. Though events begin weeks before, an evening parade formally kicks things off on the last Friday before Lent. Over several days musical acts perform on stages around the city center, and smaller ensembles wind their way through the narrow streets. Bars and restaurants mount outdoor speakers for the delight of passing revelers – a surprising number of whom opt to dress up as bananas. Naturally, these establishments profit from beverage sales, but one also stumbles across sound systems blaring late night trance and hip-hop from otherwise shuttered shops.

For all its good-natured abandon, the Carnaval in Santa Cruz is seldom mentioned alongside that of Venice or the more famous bacchanals of the Americas. This is, in part, due to the vagaries of tourism and economic development. Beginning in the 1960s, the Canary Islands emerged as a top holiday destination for northern Europeans, especially those from Germany and the UK. Many come to hike spectacular landscapes or engage in aquatic sport. Others are content simply to soak up sunlight of an intensity seldom encountered at home. In catering to the latter class of visitors, Tenerife has become rather sharply divided, with long-existing communities in the north and a southerly sprawl of resorts that can feel Spanish in name only.

By chance or design the Coso Apoteosis, or closing parade, takes place on the afternoon of Shrove Tuesday. This allows the sun and sand crowd to travel up for the day, getting back to their hotels in time for dinner and a few pints of the same lager they enjoy in Sheffield or Duisburg. While in the capital, they enjoy a pleasant enough spectacle. Yet there is little of the orgiastic spirit of preceding days and, save for the murgas (neighborhood marching associations), relatively few residents are about.

Like their compatriots, many Tinerfeños are confirmed night owls. After a long weekend of dancing in the streets, even the most ardent sybarites may find it difficult to step out before dusk. Others opt to spend all of Tuesday in reset mode, knowing that while Carnaval officially ends at midnight, there’s still more weirdness to come.

The bloody strife that preceded Franco’s dictatorship was hardly unique. The history of Iberia has been one of violent struggle dating back beyond the Moors and the Visigoths, to Hannibal and the Romans, the ancient Celts, and beyond. The artist Francisco Goya, who lived from 1746 until 1826, was not immune to this turmoil. Early in his career, Goya attracted the attention of Madrid’s elite. In 1789, he was made First Court Painter to King Charles IV, whose family he portrayed in 1800.

Some critics have depicted an element of satire in the work, but for the most part his portraits of nobility are formal and realistic. Like all of Europe, Spain was convulsed by the Napoleonic wars, and the ensuing horrors inspired a series of prints collectively known as The Disasters of War. Goya also revealed a private obsession with dark themes – insanity, homicide, and the occult. The Burial of The Sardine seems of a piece with these tendencies, though it depicts an ostensibly joyful occasion.

Wherever it is celebrated, Carnival is marked by many common elements– inebriation, masks and music. Yet El Entierro de La Sardina is gloriously and uniquely Spanish. The precise origins are the subject of much speculation. Some see it as a remnant of a mysteriously vague pagan past. Others suggest the ceremony actually originated with the burial of a roast piglet (cerdina), meant to symbolize Lenten prohibitions on pork and other meats. The most common explanation evokes the reign of Carlos III. The king, it is said, wished to mark Ash Wednesday by treating his subjects to a fishy feast. Yet the sardines spoiled before they could be distributed; the ensuing stench was such that the comestibles in question had to be dumped in a deep pit and covered with earth. El Entierro thus serves as a farewell to debauchery and to commemorate the loss of a free lunch centuries ago.

Since 1850 the inhabitants of Murcia have buried their sardines the week after Easter, but in most cities the procession is held on the first evening of Lent. Technically not part of Carnival, it is nevertheless observed with a humor and irreverence completely in keeping with the spirit of the season. In Madrid, the tradition is preserved by The Happy Brotherhood of the Burial of The Sardine, who parade in Victorian-style mourning cloaks and top hats. The Happy Brothers set out from Goya’s tomb near the hermitage of Santo Antonio de La Florida. They carry the tiny casket through the streets, stopping off at taverns and bars to sing their laments:

Sardina, Sardina, Sardina

Sardina te vamos a enterra

Sardina, Sardina, Sardina

Jamas te podremos olvidar

Sardine, Sardine, Sardine

Sardina, we are going to bury you

Sardina, Sardine, Sardine

We can never forget you

Tradition dictates that, at one point during the march, Satan appears to steal the little coffin. Dressed as policemen, members of the cofradia chase the devil away. The fish is then carried to its final resting place near the Fountain of Los Pajaritos.

On Tenerife – and in many places where the custom has been introduced – the “burial” has evolved into the cremation of a giant piscine effigy. In the hours before the immolation, mourners of both sexes fill the streets, decked out in widows’ weeds. Many clutch baby dolls, presumably the bastard spawn of the departed. Along the way, slatternly “nuns” and ersatz priests offer blessings and heretical consolation to the exhausted and bereaved survivors of another year’s festivities.

“Indianos” photo courtesy of @Lost_in_laPalma; other images in public domain.

As always, a fascinating read

Like the Hawaiian islands, which are my favourite place on the planet, the larger Canary Islands all have an unspoilt windward stretch of coast