CANDOMBE ON CANVAS

The Most Famous Uruguayan You've Never Heard Of

Last month we talked about the ways The Tradition was depicted by three very different painters – two from Europe, and one from the Caribbean. Originally, the plan was to include a South American artist as well. But as we learned more about the life and career of Carlos Páez Vilaró, it became evident he merited an issue of his own.

Vilaró was born in Montevideo, Uruguay’s capital, in 1923. Though best known for the visual arts, as a youth he was also drawn to writing and musical composition. He became a member of The Group of Eight, a movement founded to “support new tendencies in painting”. In 1959, he was chosen to decorate a corridor in the Washington, DC headquarters of the Organization of American States.

Titled “Roots of Peace” the finished work is some 155 meters long – widely considered the world’s longest mural. In terms of size and prestige, an impressive commission indeed. But the creation for which he is best known today was started a year earlier, on a significantly smaller scale. 140 kilometers east of Montevideo, the waters of the Rio de La Plata meet those of the South Atlantic. The nearby resort town of Punta del Este is sometimes called “The St. Tropez of South America” and boasts an array of trendy shops, galleries, and fine dining establishments.

In 1958, Vilaró found himself on a beach near Punta del Este, gathering driftwood planks. He used these to cobble together a small square box that would serve as a studio. Over the next 36 years, he continued to expand on it, creating a summer home for his family. Casapueblo is now a sprawling complex containing exhibition halls, a restaurant, and hotel accommodations. Guests have included the novelist Isabel Allende, sexologist Mariela Castro, and Vinicius de Moraes, the Brazilian poet and lyricist whose stage play inspired Black Orpheus.

Architectural critics sometimes compare Casapueblo to buildings found on Santorini and other Greek islands. To be sure, the resemblance is there. But Vilaró always claimed his primary inspiration was the hornero, an indigenous bird notable for building nests of mud, reinforced with grass or straw. During a 1979 interview, he elaborated on his design philosophy:

I built it as if it were a habitable structure, without plans, especially at the instigation of my enthusiasm. When the municipality recently asked me for the plans that I did not have, an architect friend had to spend a month studying how to decipher it…

As Casapueblo grew, so did the artist’s reputation. Among his friends were Pablo Picasso, Brigitte Bardot, and Gunter Sachs, a wealthy photographer and collector who clocked a brief stint as Bardot’s third husband. But in 1972, the Vilaró family made headlines for reasons that had nothing to with global glitterati.

A Uruguayan Air Force plane was chartered to take players and supporters of the Old Christians rugby club to a match in Santiago, Chile. Among those on board was Vilaró’s son Carlitos. On October 13th, the plane crashed in the Andes. Carlos Páez Vilaró joined the search and rescue mission, but the effort was called off after 8 days, having failed to locate the wreckage.

It was widely assumed that the passengers and crew – 45 individuals in total – all perished. 29 people died immediately or as a result of injuries. Amazingly, there were 16 survivors. They managed to stay warm, fashioning sleeping bags out of quilted insulation from the plane’s tail section. As rugby player Nando Parrado recalled in his memoir:

Carlitos took on the challenge. His mother had taught him to sew when he was a boy, and with needles and thread taken from his mother’s vanity case, he began to work. To speed up progress, Carlitos taught others to sew, and we all took our turns…

Almost two months after the crash, Parrado and two others set out to find help. For seven days they hiked through mountain passes before encountering Sergio Catalan, a Chilean muleteer. Catalan rode west for 10 hours, and a helicopter was dispatched. The last survivors were rescued on December 23rd, 1972.

The ordeal was dubbed “The Miracle of The Andes”, but joy was soon mixed with horror. It was revealed that they had been forced to consume the frozen flesh of their relatives and friends. A gory detail for the world’s tabloids, and an additional source of trauma for those involved. As a media circus swirled around them the survivors, all raised Catholic, received a telegram from Pope Paul VI. They had committed no sin, the Holy Father explained. Further, he said that if they had not taken the nourishment that was available, it would have been tantamount to suicide.

Talent and imagination brought Vilaró a degree of privilege and international fame, but he always retained an abiding respect for his hometown’s vibrant street culture. About 5% of Uruguay’s population identifies as Black – a small figure compared to Brazil, Colombia, or Guyana. Small though it is, the Afro-Uruguayan community has had an enormous influence on the national identity. This is especially obvious during the festive season.

Visitors to the capital almost inevitably make their way to the Mercado del Puerto. There, a number of restaurants offer asado, a feast of grilled meats that is also popular in neighboring Argentina. Not far from the mercado, one finds Montevideo’s small but fascinating Carnival museum. Opened in 2006, El Museo del Carnaval features a collection of historic costumes, performance space, and art inspired by the pre-Lenten party.

One of Vilaró’s most vibrant works pulses with hues of orange, yellow and red. Revelers from the barrio cavort with folkloric figures. There’s Gramillero, a sort of witch doctor recognized by his top hat, distinguished white beard, and a satchel filled with herbal remedies. Mama Vieja brandishes a parasol and fan. El Escobero is variously described a street sweeper or broom-maker; either way, he twirls his signature talisman in a manner not unlike a high school majorette. And of course, there are drums.

Candombe is the heartbeat of Uruguay’s Carnival. The rhythm is propelled by drums of varying sizes and tone – piano, repique, and chico. The instruments are played by hand or beaten with sticks. Accompanied by costumed dancers and colorful banners, ensembles known as comparsas gather during llamadas, or “calls”. In the colonial era, enslaved Blacks were allowed to gather freely, to enjoy the various customs of their west African homelands on the Feast of Epiphany. Over time, llamada processions during Carnival have been embraced by Uruguayans of all ethnicities. Given a shared focus on drumming, it is perhaps understandable that the practice might be confused with Candomblé, an Afro-Brazilian faith. As the journalist Ana Laura De Brito explains, the parades in Montevideo are social rather than religious in nature. Nevertheless, they do serve a deeply spiritual purpose.

This becomes obvious when one watches Candombe: Tambores en Libertad. For the 2001 release – which can be translated as “Drums At Liberty” – Vilaró collaborated with Hassen Balut and Silvestre Jacobi. The film is less a documentary than a meditation on music, and the way it invigorates a neighborhood that has seen better days. Lagrima Rios, a chanteuse at 76, explains “I was born singing. From here I will pass away into the other world. I am happy because I sing, and I will die happily, singing”.

We also meet drum maker Bienvenido Martinez. As younger man, he had a day job, practicing his craft only on weekends. Since retiring, he devotes practically all his time to percussion instruments, getting to his workshop around 10 each morning, and leaving at midnight or later. “I manage my own schedule; I start at the time I want” he brags. “But I work very long hours”.

Vilaró brought a similar energy to his efforts across multiple media. He died in 2014, at the age of 90. Interviewed soon after, his son told a reporter “I hope he rests in peace. I’ve never seen a guy who works that much, and I mean it. He worked up until yesterday”

:::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::

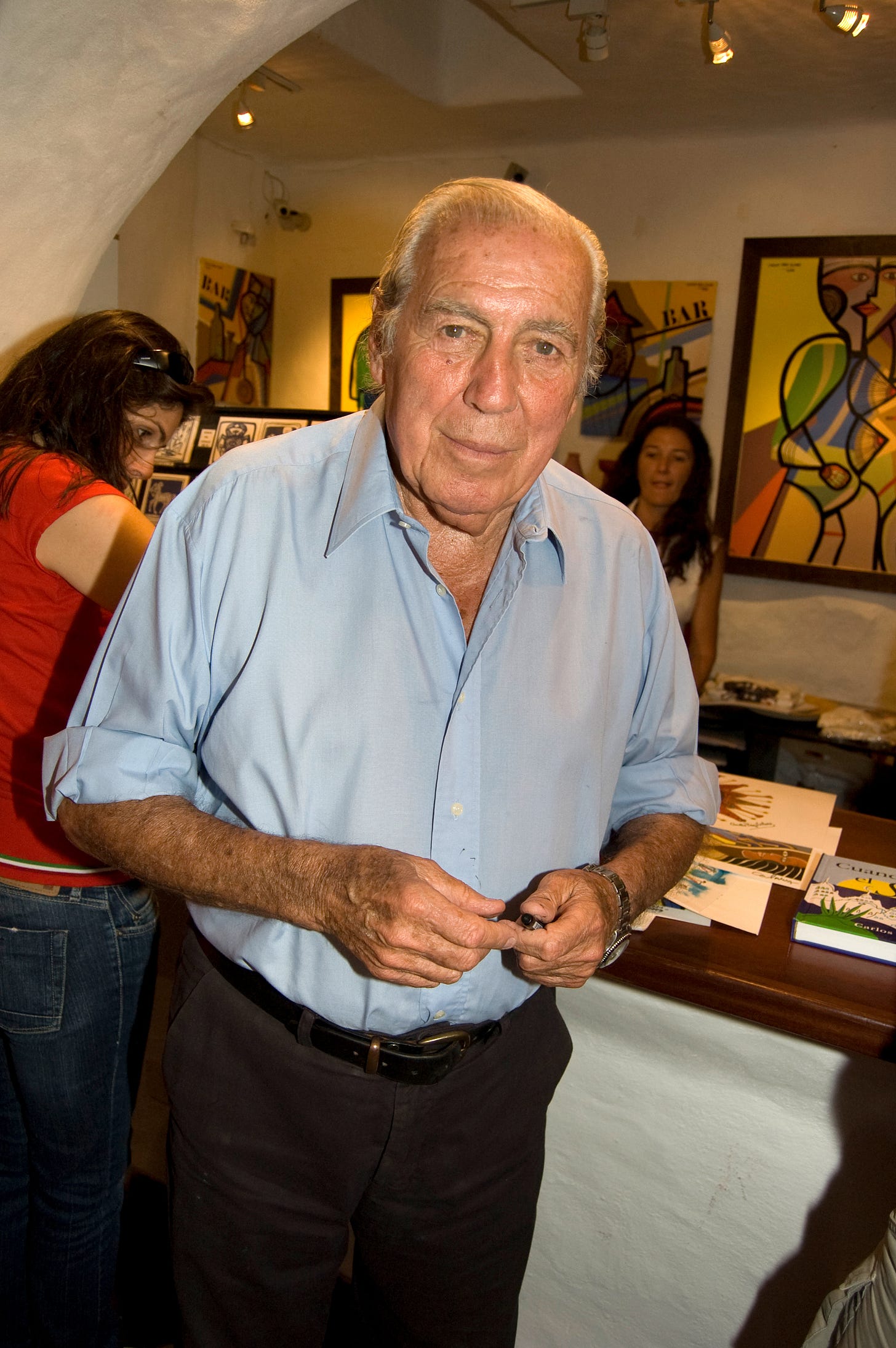

Artist Portrait: Wagner T. Cassimiro via Wikimedia Commons

OAS Mural photos: Juan Manuel Herrera

Wonderful piece! I wish my mother (who was an artist herself) could read it. Brought up in close by Buenos Aires, she spent weeks at a time in Montevideo and on the beach at "Punta" as it was affectionately called.

Terrific piece. Thank you!