OVID, THE OSCARS, & BEYOND

How a Bronze Age legend from the Balkans became an icon of Carnival around the world

A Few seconds say it all, even before the first line of dialogue. The screen fills with a marble frieze, pale figures of a man and woman. Plucked notes, melody in a minor key: guitar music, but suggestive of a lyre. The title appears, quickly establishing a link to classical civilization, as filtered through the Victorian consciousness.

With an abrupt explosion – “dissolve” can not convey the quickness of this cut – we are blasted by color and sound. In bright clothing, barefoot or wearing sandals, people of African descent make their way along a rough footpath. They play tambourines and other tools of portable percussion. Stone cottages dot the rugged hillside above a glittering sea. Only in the far background do we see the outline of modern buildings – Rio de Janeiro toward the end of the last millennium.

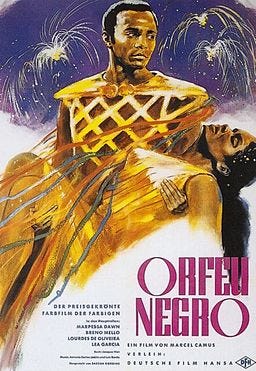

Black Orpheus, directed by Marcel Camus, won the Palme d’Or at Cannes and the 1959 Oscar for best foreign language film. The score helped fuel a worldwide interest in Brazilian music. Every artist who has recorded a version of “The Girl from Ipanema”, and anyone who has danced to the lambada, owes a debt to Black Orpheus.

Ultimately derived from classical mythology, Camus’ film is the tale of Orfeu, a Rio tram conductor, and his doomed love for Euridice, a rustic beauty who arrives in the city as Carnaval reaches its zenith. On one level, we have a cinematic cliché that predates the cinema: Boy meets Girl, Boy loses Girl, Boy tries to rescue Girl from underworld’s stygian depths.

After the montage of the opening credits, action begins with a shot of a crowded ferry approaching a wharf. Some travelers dance on the deck, but our heroine is hardly in a party mood. Euridice’s apprehension may seem typical of any country girl, arriving alone in a big city. When a kindly peddler startles her, we begin to understand the extent of her agitation. We do not yet know the reason for her fear – indeed, the precise nature of her peril remains ambiguous throughout the film.

Euridice makes her way from the boat through a marketplace that seethes with commerce and anticipation. Music abounds, masks are worn, but the excitement is of a piece with workaday life. An onion vendor shouts “cebollas, cebollas” and the cadence of her trade becomes a counterpoint to the pulse of a passing brass band. One of Camus’ triumphs is his surprisingly realist aesthetic. Black Orpheus is a movie full of singing and dancing, but it can hardly be called a “musical”; blatant choreography is conspicuous in its absence.

Next we see a bird’s eye view of Euridice crossing the empty plaza before a modernist skyscraper. Camus largely avoids the Marxist-inspired polemics that informed other auteurs of the French new wave. Indeed, many have criticized Black Orpheus for glossing over the real miseries endured in Rio’s slums. Yet in this brief shot, it is hard not to see a comment on the isolating aspects of existence in the industrial age

Over a 50 year career, Caetano Veloso – a composer, performer, and key theorist of the Tropicalia movement -- established himself as once of the leading figures in Brazilian popular music. His 2002 memoir Tropical Truth records the broad appeal of Camus’ project:

When we arrived in London in 1969, the recording executives, hippies, and intellectuals that we met all, without exception, would refer enthusiastically to Black Orpheus as soon as they heard we were Brazilians.

Veloso writes fondly of the music featured in Orfeu do Carnaval, but he is acidly critical of the film itself. Veloso was 18 when the movie premiered in Brazil; he claims the entire audience was both appalled and amused by what they saw. “We were shamed” he recalls, “by the shameless lack of authenticity”.

Ruy Castro, a journalist and historian of bossa nova, is one of many to have made a similar, if more nuanced critique. The film’s “dreamy reality”, he argues, contains no hint of mosquitoes, houses made of cardboard, the stench of open sewers. “People just loved it abroad. They come here expecting to find that kind of atmosphere”.

It would indeed be foolish to take Black Orpheus as a documentary representation of Rio de Janeiro’s poorest neighborhoods. Yet this does not invalidate it as a work of art. West Side Story is not exactly a sociological investigation of violence in mid-century midtown. For that matter, Romeo and Juliet – the basis of Bernstein’s opus -- is hardly an authentic portrayal of renaissance Italy. Yet all three are worthy and moving entertainments.

Who then is Orpheus? How is it that a figure from the Aegean world came to inspire a film set in South America, with characters and actors whose own ancestors were brutally ripped from homes in Angola and Mozambique, Benin and Ghana? What is it about a Bronze Age legend that makes it such compelling introduction to the amplified and uploaded celebrations of our own time?

As it has come down to us, the Orpheus myth owes much to the Roman writer Publius Ovidius Naso. In Metamorphoses, Ovid relates that the singer was born to a mortal king and Calliope, the muse of epic poetry. Orpheus grows to fall in love with Eurydice. Strolling through tall grass at their wedding feast, she is bitten by a poisonous serpent and dies. Grief-stricken, Orpheus goes to hell – and back.

Lyre in hand, the bereaved musician journeys to the realm of Hades. His voice and playing are so sweet that he charms the lord of the underworld, and his wife Persephone. They permit the minstrel to return with his bride to the sphere of the living – with the condition that Orpheus not look upon Eurydice until their journey is complete. This proves too much for our hero, who gazes at his beloved just long enough to see her vanish forever. Devastated once more, Orpheus vows eternal loyalty, forsaking all other women. (In a detail omitted from most post-classical tellings, Ovid explains that he transfers his affection “To youthful males, plucking the first flower/ In the brief springtime of their early manhood”).

His skills remain undiminished. Indeed, Orpheus’ gifts thrill the Maenads, the all-female worshippers of Dionysos. Enraged by the minstrel’s rejection, the Maenads attack. First they slaughter the birds and wild beasts who have gathered around, enchanted by song. Next they turn on Orpheus, pelting him with rocks and branches before tearing him to pieces. His head and lyre float down a river to the sea. The strings continue to pulse, the lifeless tongue still singing a mournful air. Bleak and strange as it is, the legend speaks eloquently of music’s power to inspire empathy or violent frenzy, to overcome death itself.

The tale was well known when Ovid wrote it down in the 1st Century AD. Most accounts say that Orpheus hailed from Thrace, a kingdom by the Black Sea. To both the Greeks and the Romans, it was a place near the edge of civilization, its people little more than barbarians. Some decades before Ovid’s birth a Thracian gladiator named Spartacus led a slave rebellion that convulsed the Italian peninsula; he remains an icon of popular revolt.

Though a major figure venerated throughout the Greco-Roman world, there are indications that Orpheus represents the survival of a more primeval cosmology, one that predates the gods and goddesses of Olympus. Some versions portray the greatest of human singers as protégé of Apollo, having received his famed lyre from the god. But there are also hints of rivalry. According to one variant, Eurydice was bitten by the fatal viper as she ran to escape being raped by Actaeus, a son of Apollo. Orpheus is said to have accompanied Jason and the Argonauts on their voyage. Calliope’s son seems to have been revered as the composer of the so-called Orphic hymns, though little is known about the mysterious rites where they were performed, and only a few fragmentary texts have survived.

It hardly matters that these accounts differ in emphasis or particulars. Indeed, it is a hallmark of a great story that its resonance grows with each retelling. When Marcel Camus and producer Sacha Gordine began filming Black Orpheus, they were drawing on more that 2000 years of aesthetic tradition. A more direct influence came from the pen of Vinicius de Moraes. “I tried to make a poet’s film” the director recalled, as his film “was helped a lot by the story of a poet”.

Born in 1913, Vinicius de Moraes was indeed a poet. But that word alone does not do credit to his remarkable career. From an early age, Vinicius was equally drawn to serious verse and popular music. By 21, he had published a collection of poems and written three songs that were recorded by RCA artistes. At 23, he had secured a position with the Ministry of Health and Education. 1938 saw him studying at Oxford under a British Council fellowship.

In 1943, having passed the exam for Brazil’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs, he served as Vice Consul in Los Angeles. Later postings took him to Rome and Paris. It seems to have been in Paris that he first had the notion to bring the tale of Orpheus and Eurydice to the hillside favelas. In 1956, a stage play Orfeu da Conceicao premiered at Rio’s Teatro Municipal while the author was on sabbatical from his diplomatic mission.

Naturally, a play about Orpheus in music-mad Brazil demanded quality tunes. Seeking a proper setting for his words, Moraes recalled a young pianist he had heard playing in a nightclub. Antonio Carlos “Tom” Jobim is one of the titans of Brazilian music, his name recognized even by those unfamiliar with his compositions. For all his travels Moraes is not nearly as well known outside of Latin America. The collaboration brought both men fame and renown greater than either is likely to have achieved on his own.

It says something about the tenor of the times that de Moraes was able to balance his diplomatic duties with success as a playwright and lyricist. Such a renaissance sensibility counted for little after the imposition of Military rule in 1964. Forced to retire from government service, the poet laughed off his banishment. The purge, he explained was directed against “homosexuals and drunks” – and his fondness for the bottle was well documented. In any event, he was able to devote the rest of his life to artistic pursuits.

In 2006, Brazil’s Chamber of Deputies posthumously promoted Vinicius de Moraes to ambassador. The move was both honorary and redundant. In a sense, he’d achieved that rank decades before, when he and Jobim were enjoying a drink and admiring a passerby on her way to Ipanema beach. It was not long before her beauty had inspired a tune that is magical in any language, and English lyrics about a girl who is tall and tan. And young. And lovely...

Jobim and de Moraes also contributed to soundtrack of Black Orpheus. Inevitably, it is a meditation on music and death – making it a perfect introduction to Carnival. Harmony derives its richness from the qualities of sonic sustain and decay; every melody depends upon the interplay of sound and silence. Reflections on mortality always suggest the hope of rebirth.

For that reason, the legend of Orpheus and Eurydice has been a recurrent motif in Carnival celebrations for centuries. L’Orfeo, by Claudio Monteverdi, is often described as the oldest opera still regularly performed. The composer would eventually find employment as Maestro di Capelli at St. Mark’s Basilica, in Venice. However, his exploration of the Orpheus legend was created for the 1607 Carnival season in the nearby city of Mantua, where he served in the court of the Gonzaga dynasty.

More than 150 years later, a composer of the German baroque revisited the material. Orfeo ed Euridice, by Christoph Willibald Gluck, premiered in Vienna in 1762. The music has its charms, though a tacked-on “happy ending” is an unfortunate departure from the tragic grandeur of Monteverdi’s version.

Camus’ film sets the doomed romance of Orfeu and Euridice in the context of an escola de samba, or samba school, as the favela prepares for a Carnival spectacle. In New Orleans, the krewes that organize Mardi Gras parades and balls play a comparable role. The size, exclusivity, and seriousness of krewes vary widely. The largest, most iconic processions include motorized floats; participating demands significant personal expense on the part of members.

The Krewe of Orpheus, established in 1993, traditionally rolls the night before Fat Tuesday. Founders include Harry Connick, Jr. and his father. The younger man is, of course, a world renowned singer; the elder Connick served as the District Attorney of Orleans Parish for decades. Both are pillars of the community. However the family originally hails from Mobile; riders in “old-line” krewes like Rex or Zulu can often trace their local roots back to Colonial times.

Most Carnival balls are members-only affairs. By contrast, Orpheuscapade, a hugely popular gala that commences after the parade, is open to the public. There is little doubt that the newer “superkrewes” are sometimes derided as arrivistes behind closed doors in certain Garden District homes. By evoking the name of the legendary bard, Orpheus is linked to a tradition even older than New Orleans itself.

Arcade Fire, a Canadian ensemble, released their Reflektor album in 2013. Regine Chassagne, a singer and multi-instrumentalist, was born outside Montreal in 1976; her parents moved there from Haiti during the regime of “Papa Doc” Duvalier. At first listen, the band’s music evokes Germanic synth pop and British art rock far more than anything coming out of the Antilles. Yet Chassagne’s ancestry has been a constant influence.

The pulsing rhythm of rara occasionally emerges from the album’s rich arrangements. Yet Kanaval’s presence is a matter more of ideas than beats or chords. Win Butler, Chassagne’s husband and bandmate told Rolling Stone that

Going to Haiti for the first time with Regine was the beginning of a major change on the way I thought of the world…there’s sex and death and people dressed up as slaves with black motor oil all over their faces and chains, and there’s little kids in puffer fish outfits or dressed like Coke bottles. There’s fire-breathing dragons that shoot real fire at the crowd.

Elsewhere in the interview, Butler extols the transcendent “feeling of less of a break between the spirit and the body”. For good measure, Reflektor’s tracks include “Awful Sound (Oh Eurydice)” and “It’s Never Over (Hey Orpheus)”

Haiti and Louisiana have had strong cultural links for centuries. New Orleans-style jazz, along with blues, gospel, and other American idioms inform the hit Musical Hadestown. Anais Mitchell wrote the book, music and lyrics for the production, which debuted on Broadway in 2019.

Her telling adheres to the contours of the ancient legend, while casting the characters of Eurydice and Persephone in high relief. The play’s allusions to contemporary anxieties don’t always succeed. Nevertheless, it is an impressive achievement, garnering multiple Tony and Drama Desk awards. “Road To Hell” the tune that bookends the action, simply but eloquently captures the timeless appeal of Orpheus and his love:

It’s an old tale from way back when

It’s an old song

It’s an old song

And we’re gonna sing it again…

It’s a sad tale, it’s a tragedy

It’s a sad song

It’s a sad song…

We’re gonna sing it anyway

Fun fact: Harry’s float broke down in front of us back in 2001?? He serenaded us for almost an hour until they could fix the tractor. Nothing will ever beat that parade.

What a great deep dive on the story of Orpheus and Eurydice! I love Hadestown, and I just put Black Orpheus in my queue. I had no idea that's where Antonio Jobim became world famous.