PUNKY, REGGAE, PARTY

Notting Hill at the crossroads of musical history

Today, Notting Hill is considered one of London’s most desirable – and expensive – residential districts. This was hardly the case in the 1940s. Like so much of Europe, the British capital was devastated by wartime bombing. Eager to find work in reconstruction, and attracted by the neighborhood’s cheap rents, many West Indians made new homes in Notting Hill.

A key event in postwar history occurred in June of 1948. The HMT Empire Windrush arrived with some 1,029 passengers from Jamaica, Trinidad, and other Caribbean colonies. Subjects of the crown, they were legally entitled to settle in the UK without any special documentation. The policy remained in effect until 1973. Those migrants, and those who followed, have come to be known as The Windrush Generation.

In the wake of Brexit, these citizens and their children have been subjected to a program of harassment and deportation by the Tory government. That, however, is a scandal for another day. Throughout the 1950s and 60s migration from Commonwealth countries was officially encouraged. This is not to say all Britons embraced their new neighbors. Black Londoners encountered frequent abuse at the hands of resurgent fascists and racist hoods, many of whom adopted “Teddy Boy” fashions.

On the evening of August 29th, 1958, Majbritt Morrison – a white Swedish woman married to a Jamaican man – was assaulted at a transit station. Later that night, a throng of up to 400 white youths descended on Bromley Road and attacked the homes of West Indian residents. The violence was repeated each day until the 5th of September.

Faced with hostility, ethnic minorities everywhere find solace in the music, cuisine, and traditions of their homelands. The Notting Hill Carnival – like Caribana in Toronto and Brooklyn’s Labor Day festivities – was established to bring a spark of tropical warmth to more northerly climes. In 1959 Claudia Jones, a journalist born in Trinidad, organized an indoor review of calypso and steelpan music at the St. Pancras town hall.

The first outdoor event, in 1966, also featured steel ensembles. Like Jones, Leslie Palmer was Trinbagonian. Yet as director, he fostered the integration of Jamaican-style sound systems and other elements from across the Antilles. In the words of the broadcaster Alex Pascall, Palmer “created the bridge between the two cultures of Carnival, calypso and reggae”.

By the 1970s virtually all of Britain’s colonies in Africa, Asia, and the Americas had achieved some degree of independence. However, in terms of popular music, Caribbean and English influences remained intertwined. One aficionado was the singer and guitarist John Graham Mellor, known to the world as Joe Strummer. His father Ralph was an officer in the diplomatic service. Strummer was born in Turkey and lived in Egypt, Germany and Mexico before ever setting foot on the scepter’d isle.

A Foreign Office perk was that children could be educated in England at public expense. Beginning at the age of nine, Strummer boarded at the London Freeman School. He would later describe the institution as “a place where thick rich people sent their thick rich kids”. Despite his father’s position, Strummer’s maternal grandfather was a crofter in rural Scotland; Ralph’s own father was a railway worker. The experience of straddling the class divide would inform the singer’s worldview and his brilliant work with The Clash.

In August of 1976, Strummer and his bandmate Paul Simonon decided to visit the Notting Hill Carnival. The local constabulary did not exactly share their enthusiasm for the irie vibes. So-called “Sus Laws” permitted the detention of individuals on the mere suspicion of criminal intent. The 1976 Carnival was patrolled by some 3000 police officers – a tenfold increase from the prior year. When a Caribbean youth was accused of being a pickpocket, simmering tensions exploded in a volley of bricks and bottles that left 160 people in hospital.

The violence at Notting Hill, and rise of punk rock, have both been described as symptoms of social upheaval as the sun finally set on the British Empire. A simplistic analysis, no doubt. 1977 was the Silver Jubilee of Elizabeth II’s reign. It would prove to be loud, angry, and historic in a way Her Majesty’s Government could not have anticipated.

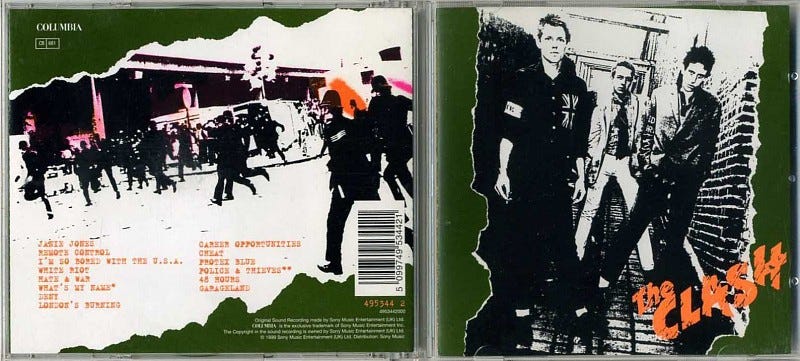

The Clash’s first album was released on April 8th. The cover art included a photo by Rocco McCauly, showing officers charging revelers at the previous years’ Carnival. Original tracks like “Career Opportunities” “White Riot” and “Garageland” fiercely embodied Britain’s punk aesthetic. The disc also included a cover tune expressing solidarity with an island far away.

“Police & Thieves” was released in Jamaica in May of 1976. Junior Murvin sang the tune in a smooth falsetto style. The Clash’s rendition was more abrasive. Both recordings depict a world where it’s hard to tell The Good Guys from The Bad:

Police and thieves in the streets

Fighting the nation with their guns and ammunition

Police and thieves in the streets

Scaring the nation with their guns and ammunition

With subsequent albums, The Clash would prove themselves the most stylistically adventurous group of the era. For sheer shock value, however, they were eclipsed at the time by The Sex Pistols. Their Single “God Save The Queen” denounced the sovereign as the figurehead of a “fascist regime” presiding over a realm where “There’s no future in England’s dreaming”.

In early June, manager Malcolm McClaren chartered a boat so the band could perform while sailing down the Thames – two days before the queen was to make an official cruise along the river. Arrests were quickly made, but the controversy pushed the song toward the top of the charts, despite a BBC broadcast ban.

The track was included on Never Mind The Bollocks, Here’s The Sex Pistols, their only album, released the following October. Debut LPs by both The Clash and Pistols would alone have been sufficient to make London the center of the musical world. But in 1977, the city was also home to an artist whose global influence would outstrip both acts: one Robert Nesta Marley.

Then as now, Jamaica recognized the queen as Head of State, but the nation had been independent for almost 15 years. With his band The Wailers, Marley raised reggae’s profile around the world. To casual listeners, the sound evoked a tropical paradise, perfumed by ganga, drenched in sunshine. These are, of course, aspects of island life. Nevertheless, the genre’s great performers have never shied away from more disturbing themes.

Over the decades power in “Jamrock” has passed back and forth between two political factions. Despite its name, the Jamaica Labour Party leans to the right. They accuse the People’s National Party of sympathies with communist Cuba. The PNP, for their part, consider their rivals CIA pawns. Ideology aside, both parties have employed armed gangs to bolster control of urban districts. Partisan firefights have been a recurring scourge across Kington.

As Rastafarians, Marley and his bandmates disdained both sides. When PNP leader Michael Manley proposed the Smile Jamaica concert to promote healing in the ravaged capital, The Wailers agreed. The concert was scheduled for the 5th of December, 1976. Soon thereafter, a general election was called. Much to the band’s dismay, the timing was interpreted as an endorsement of Manley.

Despite the optics, they carried on. After rehearsal on December 3rd, gunmen shot Marley, his wife Rita, and two others at their Hope Road compound. All four survived; the assailants have never been definitively identified. Eschewing the perils of a second assassination attempt, the concert took place as planned. Onstage, Marley took off his shirt, revealing his wounds to a crowd of 80,000. Soon thereafter, he and his entourage sought refuge in London.

During the course of an interview, journalist Vivien Goldman played The Clash’s “Police & Thieves” for Marley and Lee Scratch Perry, the dub genius who produced the original. Marley immediately felt an affinity. “Punks are outcasts from society” he said. “So are the Rastas. So they are bound to defend what we defend".

Perry reportedly was less impressed. However, he agreed to work on a new single, “Punky Reggae Party” that celebrated the post-imperial zeitgeist:

Wailers will be there

The Jam, The Damned, The Clash

Maytals will be there

Dr. Feelgood, too...

Before parting ways in 1982, the original line-up of The Clash would release 5 studio albums, numerous singles and EPs. Caribbean motifs were common. Strummer recorded Marley’s transcendent “Redemption Song” with his band The Mescaleros, and again with Johnny Cash. Punk’s evolution toward new wave coincided with a rightward turn that brought Margaret Thatcher to power. Music provided a vibrant counterpoint to The Iron Lady’s divisiveness. Acts associated with the Two-Tone label introduced ska to wider – and whiter – audiences. Movements like Rock Against Racism and the Anti-Nazi League both tempered and reflected the polarization of the times.

In 1981, at the age of 36, Bob Marley died of cancer. The 50-year-old Joe Strummer would succumb to heart disease in 2002. In the years since, the popularity and visibility of the Notting Hill Carnival have continued to increase. Zadie Smith, the brilliant chronicler of multi-ethnic Britain, used the celebration as a backdrop for her 2012 novel N.W. The onset of coronavirus led to cancellations in 2020 and 2021. NHC is set to make a glorious return during the Bank Holiday weekend, August 27-29th.

The BBC and other outlets will cover the bacchanal, while flesh and feathers will abound across Tik-Tok, Instagram, and Twitter. Technology allows revelers to share their jubilation around the world in real time, even as it has hastened the commodification of Carnival. Like the UK tabloids of the 70s, the corporate interests in control of social media profit from manufactured outrage. If past years are any indication, pics of mas costumes and videos of couples winin’ in the streets will trigger heated comments about the limits of inclusion, diaspora wars, and that most facile of bugbears, “cultural appropriation”.

Such polemics are not entirely without merit. However, they seem very far removed from that London of long ago, a metropolis where punks and Rastas discovered enduring bonds of mutual respect.

Pukny Reggae Party is a good song. I had not appreciated it fully. I think I had heard it before, but I was not fully aware of the circumstances.

What a great read. It had simply never occurred to me that there'd be a link between these things.