THE VENIAL VENETIAN

The notorious libertine Casanova had a fling or two...and a thing or two to say

The bacchanalian tradition in Venice is as renowned as that of Rio or New Orleans, and far older than either. As early as 1353, Venice’s Carnival was described in The Decameron, a collection of bawdy tales authored by Giovanni Boccaccio. For over 1000 years, “The Most Serene Republic” enjoyed independence and prosperity. That ended in 1797, when forces loyal to Napoleon invaded. The French abolished the institutions of the Venetian state, including Carnival. This policy was maintained by the Austrians, who took over in the wake of Waterloo. Venice was absorbed into the Kingdom of Italy in 1866, but public celebrations would not be revived until the 1970s.

Given this legacy, it is fitting that on the penultimate night of one recent Carnevale, clouds of theatrical smoke wafted over Piazza San Marco. On stage, a sequined ensemble known as Max and the Seventh Sound played hits by the likes of The Bee Gees and Kool & The Gang. The basilica of Saint Mark echoed with rhythms that would have delighted the denizens of Studio 54. Despite exhortations that “you should be dancing”, there were no credible reports of the evangelist fetching his boogie shoes.

Odd though it may seem, such nostalgia can help us to understand the lure of Carnival in Venice. For all the glamour of Halston and the hustle, New York was also a place wracked by successive crises – financial disarray, garbage strikes and soaring crime, the blackout of ’77. Tony Manero’s Brooklyn might have smoldered with Saturday Night Fever; off screen, the Bronx was simply burning.

The modern Carnival self-consciously evokes the 18th century. One comes across a full range of costumes: sheep and Simpsons, Mexicans and hussars. Yet the default wardrobe is a baroque pastiche. It is understandable that Venetians may wish to memorialize the last days of the republic. Even before the arrival of Bonaparte, “La Serenissima” had been undergoing a long decline.

At its zenith, Venice controlled a large chunk of Italy and the Adriatic coast, as well as Crete and Cyprus, numerous smaller islands and parts of mainland Greece. This dominion was eroded by the rise of the Ottomans to the east and other western powers. By 1720, autonomy was preserved only through constant diplomacy and occasionally, outright appeasement.

If disco teaches us anything – admittedly, a big “if” – it is that cities in decline can still be a lot of fun. This, in any case, is the impression one gets from one native of the lagoon. Giacomo Casanova was born in 1725 in the parish of San Samuele, not far from the Grand Canal. Today, Casanova is best known for his prodigiously documented sex life. Indeed, his reputation as a serial fornicator is so firmly established that many are surprised to learn he actually existed.

“I have always loved highly savory dishes” he wrote, “such as macaroni made by a good Neapolitan cook…as for women, I have always found that the one I loved smelled good, and the stronger her perspiration, the sweeter she smelled to me”.

The indulgence of appetites – gustatory, olfactory, and otherwise – seems not to have completed dissipated the author’s energy. The complete manuscript of Casanova’s autobiography ran to 3600 pages; published editions run to as many as 12 volumes. Even this is an incomplete record. The great lover died in 1798, having survived the collapse of the republic by less than one year.

The juxtaposition of pasta and passion is jarring, but such frankness gives Giacomo’s amorous recollections a power one seldom finds in fictional erotica. Even the most unbridled pornographer could hardly conceive such a range of characters. His dalliances include a young Russian serf and an elderly marquise in Marseilles. At one point he carried on clandestine affairs with not one but two nuns from the same convent.

Casanova is not always noble in the pursuit of satisfaction, but he seldom comes across as predatory or boastful. Even transitory trysts are recounted with a surprising degree of intellectual and emotional respect. Of course, we do not get the perspective of his bedmates. Yet it is easy to believe that such successes owed much to a genuine (or convincingly feigned) sensitivity.

Reading The Story of My Life, it is clear that the author was driven not just by lust but by wanderlust. After youthful consideration of a clerical career, Casanova went into public service as a sort a sort of naval attaché on the island of Corfu and at Constantinople. In the Ottoman capital, much of his time is spent in philosophical and religious discussions with Yusuf Ali, a wealthy merchant. Of course, he also finds time to gratify himself, spying on harem girls as they bathe.

Ultimately, his diplomatic record did not keep him from running afoul of the state inquisitors. In the summer of 1755, Casanova is thrown into The Leads, a notorious prison directly beneath the roof of the Doge’s palace. After 15 months he manages to escape. This jailbreak made him a fugitive as well as a celebrity; Giacomo published the tale of his daring exploit after he got tired of recounting it to acquaintances.

Even without the naughty bits, the autobiography is a fascinating romp across the continent. Casanova discusses poetry with Voltaire, fiscal policy with the King of Prussia, calendars and astronomy with Catherine the Great. And he has a thing or two to say about Carnival.

One might not expect a son of Venice to have been impressed by proceedings at the frigid periphery of Catholic Europe. Yet Casanova visited Poland in the autumn of 1765, and seems to have truly enjoyed himself in the realm of Stanislaw Augustus. The king himself is described as a man of extreme affability whose “subtle wit spread joy among all those who listened to him”. As for his capital, we learn that “Warsaw became quite dazzling during Carnival”.

Despite his incarceration and exile, Casanova remained proud of his native archipelago. Patriotism, however, did not keep him from becoming an avid Francophile. Taken by the fashions of the ancien regime, he sometimes adopted the title of Chevalier de Seingalt. The Story of My Life was written in French.

An interesting passage demonstrates the wide and enduring appeal of Venice’s celebratory spirit, even among Parisian sophisticates. An acquaintance brings him to witness Les Fêtes Vênitiennes an “opera-ballet” composed by Andre Campra:

The action took place on a day during Carnival, when Venetians gather in Piazza San Marco in masks: there were gallants, procuresses and girls who were hatching and unhatching amorous intrigues. Everything about their costumes was wrong but amusing. What made me laugh most was to see the Doge and his twelve Councilors enter from the wings decked out in bizarre togas and begin to dance a passacaglia.

His amusement does not extend to the set; the Palazzo Ducale is depicted on the left of the stage, the famous bell tower on the right. More damning still is the music itself, full of “monotony and pointless shrieks”.

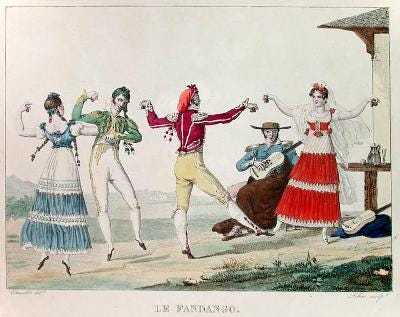

Later, the great libertine finds himself in Madrid, where Carnival season provides the background for one of the most erotically charged parts of the entire Histoire. At a pre-Lenten ball, he first encounters “a dance that so inflamed the soul” – the fandango. Surprised to find such sensuality in the land of The Inquisition, he immediately hires an instructor. Once mastering the steps, there is the pressing matter of finding a suitable partner.

This is accomplished with a peculiarly Latin sort of pragmatism. One Tuesday morning the rakish Giacomo attends mass at the church of La Soledad. A tall young beauty- Ignacia- emerges from a confessional with a contrite expression. When she kneels to do penance, our chevalier concludes “she must dance the fandango like an angel”.

Rather than approaching, Casanova follows her home. Later, he rings the bell and presents himself to Don Diego, a cobbler of noble aristocratic ancestry. Disingenuously, the author asks if perhaps the Spaniard might have a daughter willing to accompany a foreigner to the local festivities. Convinced that his visitor is a man of honor, el zapatero grants permission – and agrees to mend the gentleman’s boots. An innocent enough beginning. Yet the fandango is the fandango, Casanova is Casanova, and Carnival is Carnival…

The conquest of young Dona Ignacia is something of a mid-life crisis for the aging Italian, but Casanova also shares sordid tales from his younger days. Following dilettantish dabbling in matters of church and state, the 21-year-old was back in his old neighborhood, playing the violin at a local theater. This was hardly considered a respectable vocation; after each evening’s performance Giacomo and his masked colleagues dedicated themselves to dissolution and nocturnal pranks. Il Carnevale rolls around, providing the pretext for an episode which, in Kubrickian terms, is somewhere between Eyes Wide Shut and A Clockwork Orange.

The companions stumble into a magazzeno, a type of all-night tavern noted for a cheap but limited selection of wines. They spy a local weaver relaxing with two colleagues and his pretty young wife. Posing as an official of the Council of Ten -- a tribunal of the republic’s government -- one of the debauchees orders the men outside. A gondola is hired, and the three weavers are abandoned on an island across the lagoon.

The woman is taken to an inn in the Rialto district where she is plied with refreshments and “amorous respects”. What follows is hardly a master class in the art of seduction. It is, to use the parlance of our times, a gangbang.

We are told that the weaver’s wife enjoyed her “happy fate”. This is an uncomfortable incident, even if we accept that the seven-fold coupling was fully consensual. It likely, however, that Casanova’s contemporaries would have been less shocked than modern readers. The fact is that Venice had long been viewed as a sort of Gomorrah on the Adriatic, where venality of this magnitude was typical.

That, however, is a subject for another issue.

How fascinating .. Thank you for a glimpse into Casanova’s autobiography. I do remember going on a guided tour of the jail and the stories

" If disco teaches us anything – admittedly, a big “if” – it is that cities in decline can still be a lot of fun". Love that!

This is an engrossing and meticulously researched piece- thank you.

Thank you also for sufficient of a summary of Casanova's intimidatingly long autobiography that I can now cross it off my to do list!