This issue drops just after Memorial Day, the US holiday that marks the traditional start of summer. The idylls continue until Labor Day, observed on the first Monday in September. Like their compatriots from Atlanta to Anchorage, New Yorkers celebrate in various ways – trips to the beach, backyard barbecues, watching Major League Baseball’s regular season wind down. For many Brooklynites, the day also coincides with the big parade organized by the West Indian American Day Carnival Association (WIADCA).

The official procession generally kicks off around 11 AM, but it is preceded in the early morning hours by the local version of Jouvert. Like its namesake in Port of Spain, this is a rough-hewn, improvisatory affair. Yet in Trinidad, Carnival Monday marks the point when serious liming begins in earnest and the madness kicks into high gear. By contrast, Labor Day comes at the end of a long weekend. In 2015, festivities included performances by soca luminaries David Rudder and Bunji Garlin, a steelpan competition, and dance parties at bars and clubs around the borough. By the time the sun rose over Crown Heights, there had been three days of merriment, along with countless opportunities for jealousy and rejection, for new resentments to flare up, for old grudges to be revisited.

According to the New York Police Department, gunfire – 30 shots – rang out around 3:40 AM on September 7th. Initial reports suggested that revelers were caught up in a feud between affiliates of the Crips and a gang known as Folk Nation. Among those running for cover was Corey Gabay, a 43-year-old attorney in the administration of Governor Andrew Cuomo. Mr. Gabay took shelter behind a parked vehicle but was struck in the head. He died nine days later. The following June, three men in their early 20s were indicted on various charges. In 2018, Kenny Bazile and Micah Alleyne both found guilty of manslaughter and criminal possession of a weapon; Stanley Elianor was convicted of reckless endangerment.

The child of Jamaican parents, Gabay was raised in a Bronx public housing project. Accepted at Harvard, he was elected president of the Undergraduate Council before earning a law degree. After practicing corporate finance law for several years, he went into public service. The life and death of Corey Gabay highlights the possibilities and deadly challenges facing the Caribbean-American community. But the tragedy did not come as a shock in and of itself. Rightly or wrongly, Brooklyn’s iteration of Carnival has long been associated with the potential for mayhem. William Bratton, New York’s police commissioner at the time, called the celebration “our most violent public event.”

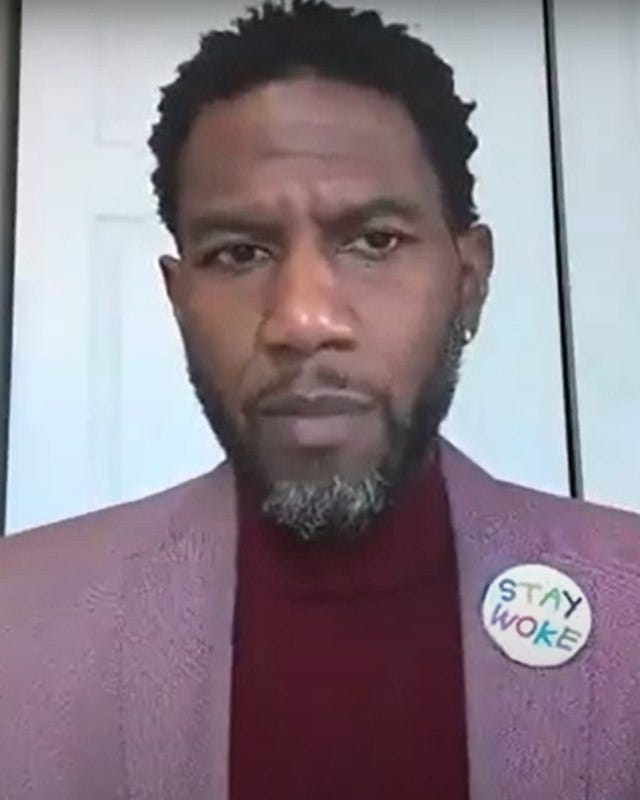

Jumaane Williams, who now serves as NYC’s public advocate, was born in Brooklyn in 1976. The son of migrants from Grenada, he grew up steeped in Carnival culture and the festivities that herald the arrival of autumn in the area. “I have been out on Eastern Parkway every year. I thought Labor Day meant Carnival, but then I got older and realized they are two different things”.

In the 2009 City Council election, Williams won a seat representing the 45th district, an area that includes multiple mas camps – where elaborate costumes are designed and fabricated - and panyards, where steel ensembles rehearse their arrangements of soca hits. He strongly backed initiatives to brand the East Flatbush neighborhood as New York’s “Little Caribbean”, where tourists can go for jerk chicken or oxtail, just as they enjoy hot dogs at Coney Island or dim sum in Chinatown. As co-chair of the Gun Violence Task Force, the councilor has developed a working rapport with the highest-ranking police officials. However, this has not shielded him from treatment all too familiar to Black Americans.

On Labor Day 2011, Williams attended the parade, as he has for his entire life. Along with Kirsten John Foy from the City Advocate’s office, he attempted to access a reception area for participants and VIPs. To do so, he needed to pass through a barricaded area between the reviewing stand and the Brooklyn Museum. Despite receiving permission to do so from a supervisor on duty, and displaying their government credentials, the men were challenged and surrounded by several NYPD officers. Foy was tripped and tackled; both men were handcuffed and held for 30 minutes before being released without charges.

The incident underlined recurrent tensions between revelers and the officers charged with protecting them. The following year, 20 police department employees were disciplined in connection with a Facebook page titled No More West Indian Day Detail. Some posts derided community members as “animals” and “savages”. One individual queried “Why is everyone calling this a parade? It’s a scheduled riot.”

Several years earlier the issue of police-community relations generated a very different type of controversy. The New York Post published photos of officers grinding up against the exposed backsides of female paraders. Reflecting on the scandal, Jumaane Williams has mixed feelings, pointing out that one of the officers (later transferred out of Brooklyn) had a history of racist comments. At the same time, he doesn’t necessarily have a problem with the idea of law enforcement representatives getting into the spirit of the day. “The theory of that behavior should be encouraged” he says, while conceding that “you probably shouldn’t mount somebody when you’re on duty”.

While not denying that terrible things have occurred, Williams thinks that much of the media coverage can be counterproductive. “Anything that happens in New York City on that weekend is blamed on the parade, but there’s violence in some of these areas every day. Focusing on one weekend doesn’t help”.

He also points out that the death of Cary Gabay was not the only tragedy to occur at the 2015 Jouvert. His hope is that people will also remember the stabbing death of 24-year-old Denentro Josiah. That still-unsolved case “got less attention, but I’m sure his family is just as sad. If this parade didn’t happen, would these folks still be alive? I don’t know the answer to that.”