JUPITER & JUNKANOO

Separated by centuries, two December holidays share affinities with Carnival

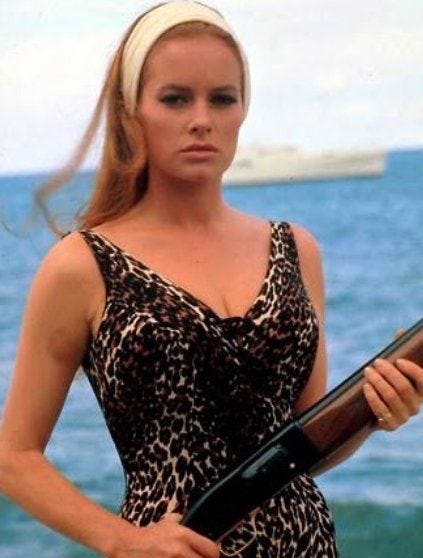

IN The James Bond flick Thunderball, 007’s eternal quest for martinis and military intelligence takes him to The Bahamas. The pursuit of nuclear-armed villains is interrupted when his taxi runs up against a rowdy street party. “It’s Junkanoo” explains Fiona Volpe, the film’s brilliantly named femme fatale, “our local Mardi Gras”.

The scene that follows displays the mix of action and exoticism that has made the franchise so popular with viewers. But is Miss Volpe’s description accurate?

Yes…and no.

To be sure, costumed revelry and distilled spirits are hallmarks of both celebrations. Punctuated by the rhythm of cowbells, whistles, and goatskin drums, Junkanoo was once common throughout the British West Indies as well as North Carolina, and Belize. It was customary for plantation owners (many of them loyalists displaced by the American Revolution) to grant their enslaved workers a few days of respite toward the end of the year.

One theory links the name to the French phrase gens inconnus (“unknown people”) – a tribute to the colorful masks worn by bands of revelers. Another explanation evokes “John Canoe”, a West African cultural hero from the early 1700s. Alternatively known as January Conny or Johann Kuny, this powerful warlord deftly exploited tensions between European traders to advance the interests of the Ahanta people, in what is now Ghana.

Nomenclature aside, Junkanoo does indeed resemble the more famous bacchanals that occur around the world – with some important differences. Mardi Gras in New Orleans reflects the Catholic faith of the city’s French colonizers. Junkanoo emerged in territories held by the Protestant English. Fat Tuesday falls right before the start of Lent; the Bahamian ritual runs from Boxing Day (December 26th) until New Year’s. Nevertheless, both celebrations echo a rite that began centuries before either.

Livy records that Saturnalia emerged in the 5th century BC. According to Roman legend, it was foretold that Saturn would be overthrown by one of his sons. Faced with this prophecy, he did what any concerned parent would do. Whenever his wife Rhea gave birth, the fierce titan would immediately devour the newborn. Rhea had Jupiter in secret, feeding her husband a stone instead. Jupiter grew to become the chief god of the Roman pantheon, and sent his father into exile.

Yet the Romans continued to honor Saturn in late December. During the celebration, the usual social hierarchy was subverted. Robert Graves, the poet and novelist, writes that “the bodily lusts [were] given full rein at the Saturnalia”. There is ample evidence from the ancients themselves that the occasion was a time of indulgence. Cato the Elder, a statesman of the republican era, writes that during the festival he provided the farmhands at his villa with an additional ration of wine, equal to an extra 20 pints each per day.

Augustus, who became Rome’s first emperor following the assassination of Julius Caesar, is said to have disapproved of gambling in general. But he apparently enjoyed sporting with dice during Saturnalia. By the reign of Domitian (AD 82-96), the Saturnalia spirit seems to have been expressed in especially elaborate gladiatorial games, combined with other public spectacles and free refreshment. It was a time, according to Statius, of “unrestrained mirth” and “lavish streams of wine”

Peter Mason, who has written extensively about celebrations in the Caribbean, states that “in Roman times, Carnival took the wild form of Saturnalia, when slaves were freed for seven days of drunkenness and allowed, theoretically at least, to exchange roles and even clothes with their masters” Mason’s assertion is often parroted by tourism authorities and the authors of travel guides. The identification is made in more scholarly works as well. The editors of the Cambridge Illustrated History of the Roman World allude to “the carnival world of the Saturnalia”.

Like Carnival today, Saturnalia was a time of merry-making. However, it would be misguided to draw a direct line from the forum to Bourbon Street or Nassau. To be sure, epic boozing featured prominently in the antique celebration. This seems to have been equally true of the Lupercal, a fertility rite observed in mid-February. Carnivalesque elements also marked the cult of Bacchus and that of Isis – an Egyptian goddess revered across the Mediterranean world.

The saturnalian hypothesis is questionable from a more obvious perspective as well. Today, Carnival is most often associated with tropical or subtropical climates. Yet it always falls in February early March – right before the onset of spring in northern temperate zones. Saturnalia, by contrast, coincided with the winter solstice. If we must identify the pagan feast with any contemporary custom, Christmas – not Carnival— is the obvious candidate.

This is not to argue that Carnival is “really” about Isis or Bacchus, rather than Saturn. In the final analysis, Junkanoo and Mardi Gras do indeed reflect an ancient heritage – but not in a narrow historical sense. Rather, those who revel at such times are manifesting something fundamental and timeless about what it means to be human.

Another absorbing piece. I love the way you put all the connections together

Thank you again, and better reason to roll the bones and drink wine during the holiday season as intended.